Temple and Tomb

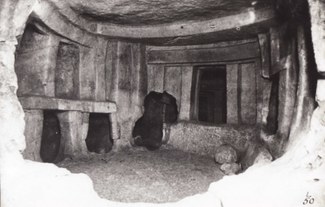

During the Temple Period, people were buried in collective underground burial sites, or hypogea (literally, “underground places”). Two extensive burial complexes have been found near the two largest temple sites, the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum near the Tarxien Temples on Malta and the Xagħra Circle near the Ġgantija Temples on the island of Gozo. Each hypogeum appears to have begun with a natural cave that was subsequently enlarged and formalized over the course of many centuries. The Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum is well preserved and includes architectural elements visually similar to those used in the megalithic temples above ground—such as the trilithon (a doorway comprised of two massive upright jambs topped by a horizontal lintel)—but carved directly into the living rock rather than constructed from blocks of stone.

Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum, main chamber, early 20th century

Courtesy Heritage Malta, National Museum of Archaeology

Eventually thousands of individuals were buried in each hypogeum. Both at the time of burial and when the bones were shifted, the remains were often liberally sprinkled with the mineral pigment red ochre, which has stained many objects to a pinkish hue. Parallels between artifacts found in the hypogea and in the temples, especially statuettes, suggest that the burial sites also held religious importance. Scholars have suggested that the red ochre symbolized blood and life, and that burial in the hypogea may indicate a belief that entrance back into the earth after death symbolized a return to the womb of Mother Earth.

Ġgantija South Temple, view of façade from the south, early 20th century

Image courtesy of Heritage Malta, National Museum of Archaeology

The Ġgantija Temples are perhaps the most impressive of all the temples in the Maltese islands, and the unrestored south corner of the monumental concave façade still stands to a height of seven meters. Construction of the temples was an immense undertaking that consumed extensive resources. The facade and exterior walls are built from massive, locally available Coralline limestone slabs, but the interior walls and decorated blocks are Globigerina limestone, which had to be brought up hill to the site from over a kilometer away. Quarried blocks were hauled to the building site on stone rollers, some of which have been discovered in the vicinity of the temples. The blocks were then maneuvred into place using levers, earthen ramps, and ropes. Most blocks weigh between half a ton to over 2 tons with the most massive estimated at 21 tons.

Mnajdra Temples, aerial view, mid 20th century

Image courtesy of Heritage Malta, National Museum of Archaeology

In this aerial view of the Mnajdra Temples, north is toward the bottom. The photo was taken shortly after restoration work was completed in the 1950s. A UNESCO World Heritage site since 1992, the structures are now protected by a carefully engineered roofing structure completed in 2011.

Each temple faces an open plaza, and the facades are often curved as if to embrace an assembled crowd. The basic temple plan consists of a variable number of D-shaped chambers, or “apses,” symmetrically arranged to either side of a central corridor that terminates in an apse or in a shallow niche. The main door and other internal doors could only be barred from the inside. The apses were roofed with partial semi-domes built of corbelled stone: layers of stone are laid horizontally, with each progressive layer extending farther inward to create a false vault. The interiors may have been entirely dark, like an above ground cave. The dimensions of the temples vary, with internal lengths between 6.5 and 23 m, and the apses measure up to 9 m in diameter. A second or third temple was sometimes built near an existing one, and the resulting complex encircled by a common outer wall.