(Session 3) "What Other Contexts?"— Liquescent Bodies and Coiffed Heads

This session will emphasize the contexts of “other” objects, including a terracotta torso from Adulis, a stone head from Berenike, and several ivory combs from Dibba and other places. Discussion leaders: Gabriele Castiglia (Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana), Anna Filigenzi & Chiara Zazzaro (Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale”), and Jeremy Simmons (University of Maryland).

This session expands the focus to the ‘other’ objects of Indian origin and style found in Northeastern Africa and Southern Arabia. These objects, several of them only recently brought to light, testify to a wider presence of South Asian-like objects in the Indian Ocean than traditionally thought. As new evidence continues to emerge, objects such as these raise further questions about the movement and the reception of these figurines.

Our first object is a small terracotta figurine from Adulis (fig. 25). This fragmentary male torso was found in what was possibly a domestic building, alongside local and imported potsherds. Anna Filigenzi and Chiara Zazzaro identified the figurine as a ‘Gupta’ period artifact and accordingly dated it between the 4th and 6th centuries CE. Although a precise identification of the subject is impossible, specific details may identify it as an attendant figure or a guardian/apotropaic figure. The figurine might have been the personal possession of an Indian person, possibly a merchant. It is, in fact, not the only object of Indian origin found in the port of Adulis, confirming the early role that coastal Eritrean sites played in the relationship between Africa and India.

In the third century CE, the Red Sea's western and eastern shores strengthened two local kingdoms: Aksūm on the west and Ḥimyar on the east. Emerging from modern southern Eritrea and Tigray, Aksūm managed to expand its territory over the coastal plains and even conquered parts of the southwestern corner of the Arabian Peninsula for a brief span of time. The heyday of the Aksumite Empire is usually dated from the third to seventh centuries. Economic decline was visible in the second half of the sixth century and was probably exacerbated by the later Muslim conquests.

The second object is a small stone head of the Buddha (fig. 26) measuring just 9.3 cm high, found at Berenike in Egypt on the western shore of the Red Sea. Found in a room alongside a “bonanza” of artifacts that included bronze, stone, and wooden statuettes in Egyptian and Greco-Roman style, archaelogists claim the head was produced by a local artisan although it is South Asian in style. Overall, the iconography seems Gandharan, Kushan or Guptan, the style of the eyes and mouth is unmistakably local, also seen on the heads of other stone statuettes found at Berenike.

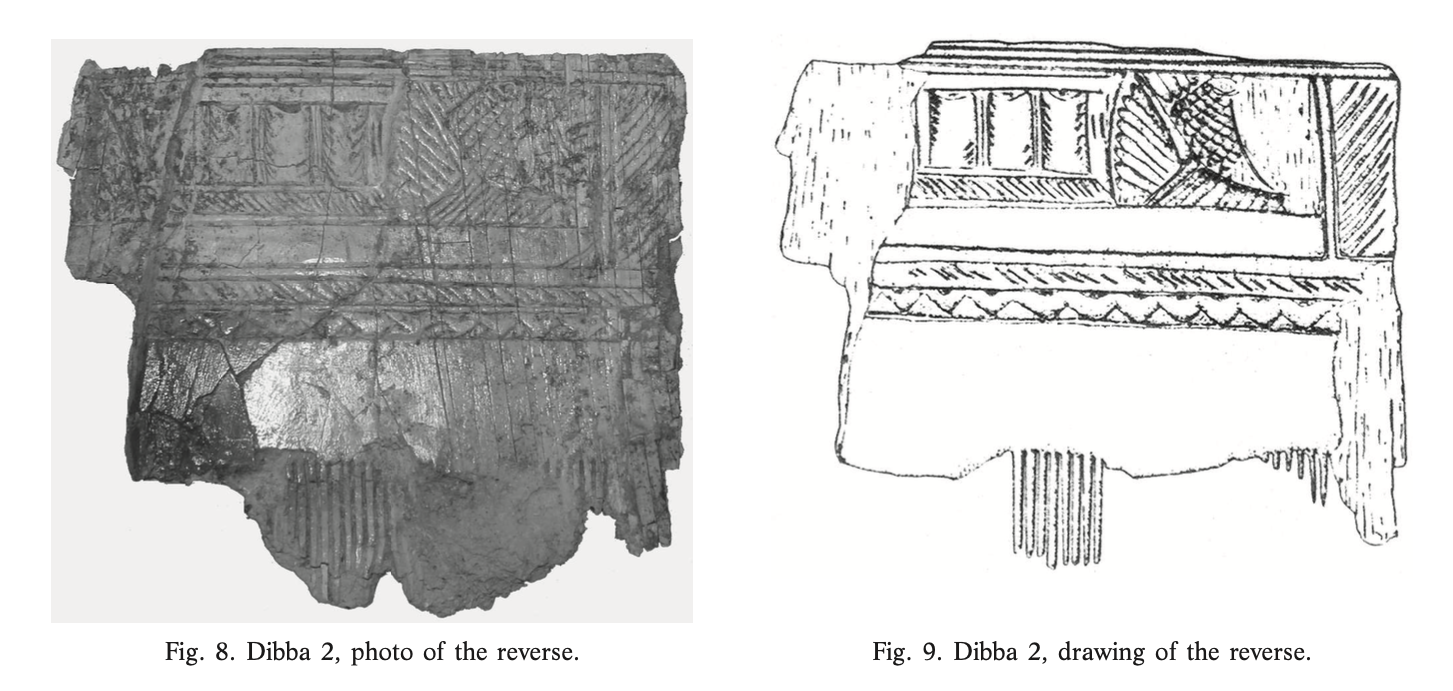

Finally, our last set of objects is a set of ivory combs (figs. 27 and 28) found in Dibba Al-Hisn in the Emirite of Sharjah on the shore of eastern Arabia. They were unearthed in 2004 in a collective tomb, which also contained other goods from Parthia and the Roman world. Since many goods involved in Indian Ocean trade were perishable—including ivory—these combs are a rare and important find, and there are very few that can compare.

Evidence of Indian products from these sites confirms the early role that the northeastern coast of Africa and eastern Arabia played in the Indian Ocean network, and a reevaluation of their significance is of essence. Similarly, looking at the Adulis figurine, the Berenike head and the Dibba combs, can shed better light on the nature of the objects coming from India to these regions, moving beyond a traditional approach that heavily prioritizes raw materials.

Object Video

Speaker bios

Gabriele Castiglia is Assistant Professor at the Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana (PIAC) in Rome. He teaches "Christian Topography of the Late Antique World" and "Methodology of Archaeological Research". He has been working in many excavations of Early Christian contexts in Italy and abroad for twenty years and has authored many publications on these themes. Since 2017 he has been directing the excavations of two of the Early Christian churches in Adulis (present-day Eritrea) and published many papers on his research about these contexts in journals such as "The Journal of African Archaeology", "Antiquité Tardive", "Vetera Christianorum.” He has a forthcoming paper in the widespread journal "Antiquity" about the Archaeology of Conversion in the Horn of Africa.

Anna Filigenzi is Associate Professor in Indian archaeology and art history at the University of Naples “L’Orientale”. She has been the director of the Italian Archaeological Mission in Afghanistan since 2004, and a member of the Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan since 1984. She is a member of several scientific institutions, in Italy and abroad. Her research, publications and teaching are mostly related to the art history and archaeology of the area stretching across the North-west of the Indian subcontinent, the Himalayan regions and Central Asia, with special focus on Gandharan and post-Gandharan periods; Buddhist iconography and architecture; relationship between religious culture, politics and civil society; cultural relationship between Northern Pakistan, Kashmir, Afghanistan, Western Himalaya and Xinjiang, particularly with regard to the development and circulation of visual art forms.

Jeremy Simmons is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Maryland, College Park. He earned his Ph.D. in Classical Studies at Columbia University and his B.A. in Classics and Near Eastern Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. He has held fellowships from the American Institute of Indian Studies, the Social Science Research Council, the American Academy in Rome, and the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. His scholarship on topics ranging from ancient Indian numismatics to the Roman consumption of Indian black peppercorns has been published in a number of academic journals and edited volumes. His continued research interests lie in long-distance maritime commerce in the western Indian Ocean during the early centuries of the Common Era. He is working on a book project that focuses on the consumption of goods traded across the Indian Ocean in antiquity, addressing representative commodities in their new social and cultural contexts.

Chiara Zazzaro is Professor of Maritime Archaeology at the Università di Napoli “L’Orientale” (Italy) where she also completed her PhD. Chiara has been researching in the field of maritime archaeology and ethnography of the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean for over twenty years. Her research interests concern ancient navigation and contacts, ancient and traditional boats, ports, and activities related to the maritime and underwater environment. Chiara has conducted ethnographic research on traditional boats and boat building traditions and communities in Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Sudan, and Indonesia; archaeological research in the Pharaonic harbor of Mersa Gawasis (Egypt, Middle Kingdom), in the harbor of Adulis (Eritrea, 2nd c. BC-7th c. AD), on the Umm Lajj shipwreck (Saudi Arabia, 18th c.), on the boat of Punjulharjo (Indonesia, 7th c. AD), and in the Gulf of Napoli (Italy). She is author of numerous publications on the above-mentioned topics.

Images

Adulis

- The site of Adulis (fig. 43)

- The so-called "British Museum Church" (likely the cathedral of Adulis) and the rooms standing immediately north of it (fig. 44)

-

Map of Adulis (fig. 38)

Berenike

-

Map of Berenike (fig. 39)

Dibba

-

Map of Dibba (fig. 40)

Discussion Questions

-

How can we identify the terracotta torso from Adulis? Iconographically? Comparisons in situ? Where could this torso have been from in the Indian subcontinent?

-

Why is the Adulis figure dated to the Gupta period? What comparanda can corroborate this dating to the Gupta period?

-

The Adulis figure is the first male anthropomorphic figure of Indian origin analyzed so far in this series. Based on the available evidence it appears that most of these mobile small figurines are female. What can be said about the possible connection between mobility, ‘exotic’ lure, and the raw nudity of these female bodies?

-

Discussions in this series have highlighted the scarcity of evidence for objects of Indian manufacture. Much of this material record of trade is characterized by an absence of many examples. How can we explain the multiple examples of ivory combs in this context of absence?

-

How can we contextualize the Dibba combs within a market context that prioritized raw materials, especially unworked ivory? Can the ivory working of this comb be in any way tied to the Pompeii figurine?

-

The Berenike head was interpreted as possibly being carved by a local artisan following South Asian iconography. Could the artisan be an Indian resident who moved with a community of merchants to Berenike? Or could it be a local artisan who had traveled to India? If not, is there archaeological evidence of other Indian objects in the region that display a similar style to the Gandharan, Kushan, or Guptan Buddhas?

-

Is the head really a representation of Buddha? If so, was the head possibly recognized by the local community of Berenike as so? Would merchants traveling in the Indian Ocean World be familiar with such religious iconography? Let’s not ignore the strong connection present between foreign merchant communities and Buddhist patronage in the Indian subcontinent. Could such a figurine be the product of a similar link?

-

Other objects found in the same trench as the Buddha head were Egyptian and Greco-Roman in style. They were primarily of religious significance, leading archaeologists to believe that they were originally dedicated inside a temple. This raises the question - why were they placed here? The small size of the room and dense packing suggest it was not a small antiquarium or museum. Were they perhaps stored for protection, or did someone place them here while clearing the temple of images no longer in use?

-

Several of these objects were interpreted as possibly being a personal belonging of Indian travelers or local residents of Indian origin, as opposed to objects imported for commercial purposes. Do the archeological contexts confirm such theory; if so, does the context tell us more about who the owner could have been?

-

Literary texts mention many examples of foreigners resident in South Arabian cities and in the island of Socotra, between the South Arabian and Northeastern African coast. Do we have evidence of foreign mercantile settlements in northeastern Africa too? If so, can we identify seasonal versus more long-term mercantile communities in the Red Sea region of the Indian-ocean world? Is there any evidence of Indian artists/craftsmen settled in the Horn of Africa? How can we trace the presence of foreigners?

-

How does the finding of these three objects expand our knowledge of the Indian Ocean cultural milieu? Several of these have been recently uncovered; can we expect in the next decade a significant increase in sculptuary evidence in the coastal towns of the Indian Ocean?

Key References

Castiglia, Gabriele. “For an Archaeology of Religious Identity in Adulis (Eritrea) and the Horn of Africa: Sources, Architecture, and Recent Archaeological Excavations,” Journal of African Archaeology. 19.1, 2021. 1-32.

Filigenzi, Anna, and Chiara Zazzaro. “An Indian Terracotta Figurine from the Eritrean Port of Adulis.” Journal of Indian Ocean Archaeology, no. 13–14, 2017. 1–12.

Kaper, Olaf, Rodney Ast, Alfredo Carannante, and Roberta Tomber. “Berenike 2019: Report on the Excavations.” Thetis, Band 25, 2020. 11-22.

Mehendale, Sanjyot. “Begram: Along Ancient Central Asian and Indian Trade Routes.” Cahiers d’Asie Centrale, no.1/2, 1996. 47–64.

Passmore, Emma, Janet Ambers, Catherine Higgitt, Clare Ward, Barbara Wills, St John Simpson, and Caroline Cartwright. “Hidden, Looted, Saved: The Scientific Research and Conservation of a Group of Begram Ivories from the National Museum of Afghanistan.” The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 6, 2012. 33-46.

Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology UW. “The Berenike Project: Polsko-Amerykańska Misja Archeologiczna w Berenike,” 2008.

Potts, Dan. “Indianesque Ivories in Southeastern Arabia.” Un impaziente desiderio di scorrere il mondo: studi in onore di Antonio Invernizzi per il suo settantesimo compleanno. Monografie di Mesopotamia 14. Firenze: Le lettere, 2011. 335-45.

Sidebotham, Steven E. Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route. California World History Library 18. University of California Press, 2011.

Wild, Felicity C., and John P. Wild. “Sails from the Roman Port at Berenike, Egypt,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 30.2, 2011. 211–20.

Zazzaro, Chiara, Andrea Manzo, Mehretab Tabo Sium, and Thomas Tesfagiyorgis Paulos. “A Preliminary Assessment of the Pottery Assemblage from the Port Town of Adulis (Eritrea)”, British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 18, 2012. 233–46.

Zazzaro, Chiara. The Ancient Red Sea Port of Adulis and the Eritrean Coastal Region: Previous Investigations and Museum Collections. BAR International Series 2569. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2013.

Zazzaro, C., E. Cocca, and A. Manzo. “Towards a Chronology of the Eritrean Red Sea port of Adulis (1st - 7th century AD),” Journal of African Archaeology 12.3, 2014. 43-73.

-----------------------

To return to the main page click here.