Excavations at Gird-i Rostam

Figure 1: Click to Enlarge Map

Had it not been for the Covid-19 pandemic this year, the first two, very promising seasons of excavation by the Joint Kurdish-German-American expedition at Gird-i Rostam in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq would have been followed in June-July, 2020, by a third season. But we all know why that couldn’t happen. Nevertheless, a pause in excavation is not necessarily a bad thing, and in our case, it has allowed us a bit more time to reflect on some of the important finds made in 2018 and 2019, one of which forms the subject of this piece.

Figure 1: Click to Enlarge Map

Had it not been for the Covid-19 pandemic this year, the first two, very promising seasons of excavation by the Joint Kurdish-German-American expedition at Gird-i Rostam in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq would have been followed in June-July, 2020, by a third season. But we all know why that couldn’t happen. Nevertheless, a pause in excavation is not necessarily a bad thing, and in our case, it has allowed us a bit more time to reflect on some of the important finds made in 2018 and 2019, one of which forms the subject of this piece.

Figure 2: Aerial photograph showing the state of the excavations

Figure 2: Aerial photograph showing the state of the excavations

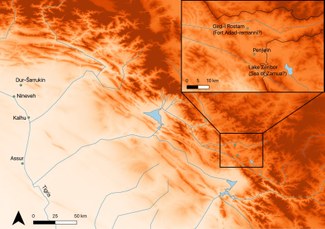

One of the attractions of working at Gird-i Rostam is its location in the far eastern reaches of the Sulaymaniyah Governate, close to the Iranian border. Although the past 10-15 years have witnessed a proliferation of archaeological projects in Kurdistan, many of these havebeen concentrated around the region’s capital, Erbil. East of the city of Sulaymaniyah itself, most of the work has been focused on the Shahrizor plain. By contrast, the region close to Penjwin, just a few miles from the Bashmaq border crossing point into Iran, has hardly been investigated. And yet, quite apart from the interest presented by this area in prehistory and late Antiquity, the Assyrian expansion into the Zagros foothills, and the Assyrian encounter with the rival kingdoms of Urartu, Mannea and Media, combine to make this an extraordinarily interesting area, and one that is virtually untouched, archaeologically speaking.

Along with obsidian of 5th millennium BC date from eastern Turkey and southern Armenia, and stamped Sasanian pottery showing Christian crosses from the late pre-Islamic era, perhaps the greatest surprise of our first season was the discovery of a small ceramic sherd with a fragmentary Akkadian inscription showing unmistakable Neo-Assyrian sign forms. The sherd comes from a typically Assyrian drinking bowl. Normally, bowls of this sort — whether of stone, metal or pottery — were inscribed with their owner’s name and/or title and were usually gifts from the Assyrian king.

Figure 3: Fragmentary cuneiform inscription from Gird-i Rostam

Figure 3: Fragmentary cuneiform inscription from Gird-i Rostam

Although the inscription is broken, the divine name dIM, that is Adad, can be clearly read in its second line. Adad, therefore, may have been part of a name, either a personal name or a place name. As it happens, a place called Fort Adad-remanni is mentioned in the cuneiform sources as an Assyrian stronghold during the reign of Sargon II (721-705 BC) and a Mannean one during the reign of Assurbanipal (669-630 BC).

The Manneans, whose heartland was probably located a bit further east in Iranian Kurdistan and Azerbaijan, were one of Assyria’s main rivals in this region, and Fort Adad-remanni was presumably lost by the Assyrians to the Mannaeans in the early 7th century BC.

Moreover, we know from a text referred to as the ‘Zamua Itinerary,’ that Fort Adad-remanni was one of the last places on the east-west route leading to the Sea of Zamua, identified by most scholars nowadays with Lake Zeribor, just a few miles to the east of Penjwin and the Bashmaq border crossing. Although still early days in our excavations, it is certainly tempting to identify Gird-i Rostam with the site of Fort Adad-remanni, a site inhabited long before and long after the struggle between Assyria and Mannea for hegemony in the western Zagros foothills.

Figure 4: Architecture exposed at Gird-i Rostam

Figure 1: Map showing the location of Gird-i Rostam, Lake Zeribor and the Assyrian capitals Image: Dr. Andrea Squitieri, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich)

Figure 4: Architecture exposed at Gird-i Rostam

Figure 1: Map showing the location of Gird-i Rostam, Lake Zeribor and the Assyrian capitals Image: Dr. Andrea Squitieri, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich)

Figure 2: Aerial photograph showing the state of the excavations at Gird-i Rostam at the end of the 2019 season, taken from a drone Image: Dr. Andrea Squitieri, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich

Figure 3: Fragmentary cuneiform inscription from Gird-i Rostam Image: Dr. Andrea Squitieri, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich

Figure 4: Fragmentary cuneiform inscription from Gird-i Rostam Image: Dr. Andrea Squitieri, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich