A Wonder to Behold: Craftsmanship and the Creation of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate

This article by Clare Fitzgerald first appeared in ISAW Newsletter 25 (Fall 2019).

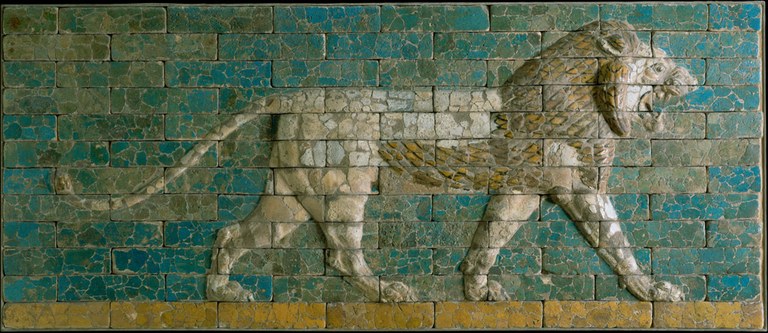

Reconstructed panel of bricks with a striding lion. Neo-Babylonian Period (reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, 604–562 BCE), molded and glazed baked clay, Processional Way, El-Kasr Mound, Babylon, Iraq, H. 99.7 cm; W. 230.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1931: 31.13.2

The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World presents A Wonder to Behold: Craftsmanship and the Creation of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate, opening new avenues for understanding one of the most spectacular achievements of the ancient world. On view from November 6, 2019, through May 24, 2020, the exhibition, which includes over 150 objects, brings to life the collaborative synthesis of masterful craftsmanship and ancient beliefs that transformed clay, minerals, and organic materials—already magically potent substances—into a protective entryway and one of the largest, most powerful monuments of ancient Babylon.

Reconstructed panel of bricks with a striding lion. Neo-Babylonian Period (reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, 604–562 BCE), molded and glazed baked clay, Processional Way, El-Kasr Mound, Babylon, Iraq, H. 99.7 cm; W. 230.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1931: 31.13.2

The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World presents A Wonder to Behold: Craftsmanship and the Creation of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate, opening new avenues for understanding one of the most spectacular achievements of the ancient world. On view from November 6, 2019, through May 24, 2020, the exhibition, which includes over 150 objects, brings to life the collaborative synthesis of masterful craftsmanship and ancient beliefs that transformed clay, minerals, and organic materials—already magically potent substances—into a protective entryway and one of the largest, most powerful monuments of ancient Babylon.

A Wonder to Behold demonstrates that the master artisans who designed and built the Ishtar Gate and its affiliated Processional Way were not only skilled technicians, but also artists, historians, and ritual practitioners who, along with other scholars and specialists, were known as “experts” (ummânū). They were believed capable of creating artworks that manifested divine power on Earth, and the Ishtar Gate, offering entry into the imperial city of Babylon, was designed to be one such magically-activated monument.

Background

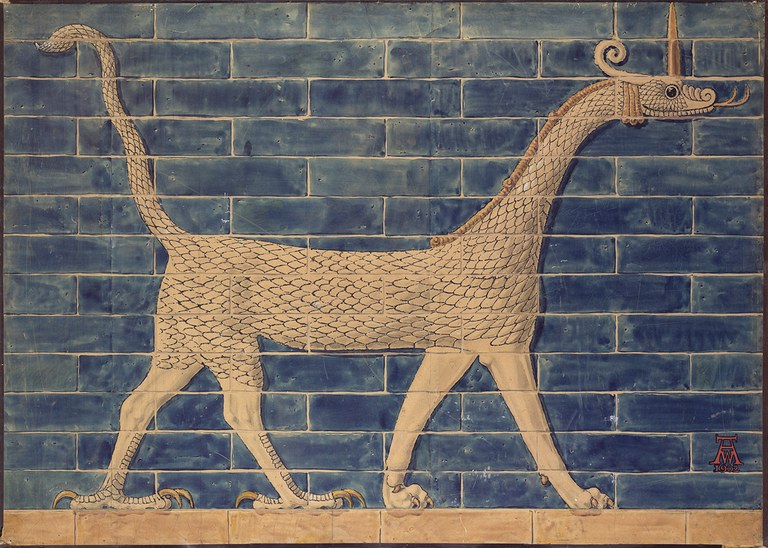

Walter Andrae. Reconstruction of bricks with a mušhuššu-dragon from the Ishtar Gate. 1902 CE, watercolor and graphite, H. 117 cm; W. 164 cm. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum: VAK 0009

Built over the course of King Nebuchadnezzzar II’s reign (r. 604–562 BCE), the Ishtar Gate (named after the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar) and the Processional Way, were among the most impressive monuments of the city of Babylon, itself the epicenter of a major empire that extended from present-day Iran to Egypt. The monument was created of brilliantly glazed bricks, molded in relief to depict hundreds of dragons, lions, and bulls—all set against a brilliant blue background. At once ritually protecting and providing access to the heart of the sacred imperial city, these creatures inspired both admiration and apprehension in viewers.

Walter Andrae. Reconstruction of bricks with a mušhuššu-dragon from the Ishtar Gate. 1902 CE, watercolor and graphite, H. 117 cm; W. 164 cm. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum: VAK 0009

Built over the course of King Nebuchadnezzzar II’s reign (r. 604–562 BCE), the Ishtar Gate (named after the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar) and the Processional Way, were among the most impressive monuments of the city of Babylon, itself the epicenter of a major empire that extended from present-day Iran to Egypt. The monument was created of brilliantly glazed bricks, molded in relief to depict hundreds of dragons, lions, and bulls—all set against a brilliant blue background. At once ritually protecting and providing access to the heart of the sacred imperial city, these creatures inspired both admiration and apprehension in viewers.

By the late 19th century, it appeared that all that was left of the Gate were glittering fragments of colorful glazed brick scattered among the rubble of collapsed clay architecture. Between 1899 and 1917, German-led excavations uncovered not only the glazed remains of the towering Ishtar Gate, but also its molded (unglazed) foundations, which extended deep into the earth. Archaeologist Robert Koldewey sent almost 800 crates of fragments to Berlin, first with the permission of the Ottoman, and later the Iraqi governments. Once there, the colorful remains were cleaned, stabilized, and sorted, then assembled piece by piece, creating first whole bricks and subsequently panels of brightly colored raised-relief beasts. These reconstructed ancient remains were joined with modern blue bricks to create a monumental reconstruction (albeit at a slightly smaller scale) of the Ishtar Gate and its affiliated Processional Way at Berlin’s Vorderasiatisches Collection, housed in the Pergamon Museum.

Today, a multi-national process of excavation, reconstruction, and conservation of the Ishtar Gate continues and the monument may be experienced both in Berlin and in its original site in Iraq. The city of Babylon, Iraq— featuring the earlier, unglazed phases of the Gate’s foundations—is now on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Since 2010, the World Monuments Fund has collaborated with local and international communities to conserve these Iraqi remains for future generations.

Exhibition

Mold for a female figurine. Middle Elamite Period, ca. 1500–1100 BCE, molded baked clay, Susa, Iran, H. 19 cm; W. 8.5 cm; D. 3 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités orientales: Sb 7413

The exhibition opens with an introduction to the gateway as revealed through its discovery and reconstruction. A 1901 watercolor by archaeologist Walter Andrae, for example, shows the Babylonian system of fitters’ marks that he deciphered, revealing the painstaking process through which the monument was created. This process began by marking out the design on a wall of unadorned bricks, and continued with the molding, glazing, and baking of each individual brick before fitting them together, a task that is something like designing and assembling an intricate puzzle.

Mold for a female figurine. Middle Elamite Period, ca. 1500–1100 BCE, molded baked clay, Susa, Iran, H. 19 cm; W. 8.5 cm; D. 3 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités orientales: Sb 7413

The exhibition opens with an introduction to the gateway as revealed through its discovery and reconstruction. A 1901 watercolor by archaeologist Walter Andrae, for example, shows the Babylonian system of fitters’ marks that he deciphered, revealing the painstaking process through which the monument was created. This process began by marking out the design on a wall of unadorned bricks, and continued with the molding, glazing, and baking of each individual brick before fitting them together, a task that is something like designing and assembling an intricate puzzle.

The Ishtar Gate and Processional Way represent the epitome of major developments in molding and glazing technologies that had taken place over the preceding centuries, enlivening architecture by bringing color and dimension to otherwise unadorned mudbrick buildings. A reconstructed panel on view here shows one of the 120+ molded and glazed lions that paraded out from the Gate and down the Processional Way. Believed to be powerful beings associated with the king’s role as protector of his people, the beasts are depicted in raised-relief, projecting into the space of the viewer as they intimidated unwelcome visitors while protecting the inhabitants of the city.

Other objects illustrate the links between the world of the gods and the Ishtar Gate through an exploration of the religious meaning of lions, bulls, and mythical mušhuššu-dragons. These include an Assyro-Babylonian cylinder seal showing the fierce goddess Ishtar, who helped protect the city from enemies, with her lion, and a marble bowl dating from 2900–2600 BCE. The piece demonstrates the continuity of the repeating bull image—which also appears of the façade of the Ishtar Gate—and its ritual significance, already understood to be ancient in Nebuchadnezzar II’s time.

Clay was endowed with vital power in the ancient Middle East, viewed as the medium of creation and tied closely to the gods. Ancient texts asserted that the first gods and first humans were created of clay, and the process of molding clay was linked to gestation and birth. Clay was also used by craftspeople to create figures imbued with life and capable of acting on their creator’s behalf, and statuettes—including molds for female figurines included in the exhibition—were often associated with fertility.

On view as well is a brick from Babylon with a cuneiform inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II that is also impressed with the paw of a wandering dog—lending us a direct, affective point of access to the ancient world. After being molded, bricks like these, which were used in official constructions, were stamped with the king’s inscription and laid out to dry in the sun and sometimes baked in a kiln. The dog print illustrates not only the malleability and receptivity to touch that are inherent properties of clay, but also provides a sense of daily life at the brickmaking yard.

Although clay is most closely identified with ancient Middle Eastern architecture, glass-like vitreous materials—such as the glaze that adorned the Ishtar Gate bricks—were also believed to be magically significant. A cuneiform tablet from the Middle Babylonian Period (ca. 1300–1200 BCE) records a recipe for making red glass that highlights the secret alchemical knowledge of ancient Middle Eastern craftspeople, while an Egyptian glass vessel from ca. 1400–1300 BCE showcases the range of brilliant colors that these experts were able to obtain through the use of vitreous materials, rivaling the qualities found in naturally-occurring stones. In fact, human-made materials were believed to be as magically powerful as naturally occurring ones, their brilliance and shine no less meaningful, and the recipes for manufacturing these magical substances were kept secret and specific rituals were prescribed to ensure a successful outcome.

Featuring sculptural brick panels, cylinder seals, cuneiform tablets, jewelry, statuettes, molds, glassware, excavation watercolors, and more, A Wonder to Behold looks at the materials, techniques, and people behind the Ishtar Gate allowing visitors to see this icon anew.