Hymn to Apollo (Winter, 2019)

This article appeared in ISAW Newsletter 23, Winter 2019. For up-to-date information on "Hymn to Apollo" and other ISAW exhibitions, please consult the Exhibitions section of our website.

Hymn to Apollo: The Ancient World and the Ballets Russes

March 6 —June 2, 2019

Hymn to Apollo: The Ancient World and the Ballets Russes explores the seminal role of antiquity in shaping the radically new creations of the famed ballet troupe founded in 1909 by Sergei Diaghilev.

Background

Ancient Greece left us tantalizing clues about the nature of dance in antiquity, with depictions of dancers in sculptures in the round and in relief, vase paintings, and other media. Yet without technical treatises or dance notation, ancient dance remains elusive, a lost art. What we do know, thanks to texts by authors including Plato, Petrarch, and Aristotle, to name only a few, is that it was performed, usually by a chorus, in conjunction with music, poetry, and theater—one component of something like what would later be interpreted as a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art; that it was central to religious rituals; and that it had the potential to express fundamental truths about the human condition.

The mysteries of the ancient rituals to which dance was integral attracted many early twentieth-century artists, choreographers, and composers, who drew freely and imaginatively from the evidence provided by artifacts and texts, creating something radically new by looking back. In this they were helped by the numerous archaeological objects entering Western European museums and other collections and appearing in newspapers and magazines during the so-called golden age of archaeology. Hymn to Apollo shows how this company brilliantly interpreted images and forms from ancient Greece, Rome, and Egypt to pioneer radically new approaches to choreography, music, costume, and stage design.

Exhibition

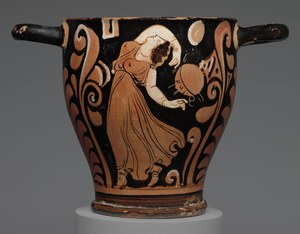

Attributed to the Frignano Painter. Skyphos with a Dancing Maenad. Late Classical, 375–350 BCE. Terracotta. Campania, Italy. H. 16.5 cm; W. 15 cm. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Dr. Harris Kennedy, Class of 1894: 1932.56.39 Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Hymn to Apollo opens with a terracotta skyphos (375–350 BCE), painted with a dancing maenad (a worshipper of Dionysus). While images like this figure did not represent actual dance steps, we can see that they did reveal poses and costumes that would offer a wealth of choreographic and formal inspiration to Ballets Russes collaborators. The dancer depicted here, for example—full-figured and wearing a loose-fitting dress, her head thrown back in ecstasy—provides a vivid image of the Dionysian passion that would inform some of the Ballets Russes best-known productions.

Attributed to the Frignano Painter. Skyphos with a Dancing Maenad. Late Classical, 375–350 BCE. Terracotta. Campania, Italy. H. 16.5 cm; W. 15 cm. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Dr. Harris Kennedy, Class of 1894: 1932.56.39 Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Hymn to Apollo opens with a terracotta skyphos (375–350 BCE), painted with a dancing maenad (a worshipper of Dionysus). While images like this figure did not represent actual dance steps, we can see that they did reveal poses and costumes that would offer a wealth of choreographic and formal inspiration to Ballets Russes collaborators. The dancer depicted here, for example—full-figured and wearing a loose-fitting dress, her head thrown back in ecstasy—provides a vivid image of the Dionysian passion that would inform some of the Ballets Russes best-known productions.

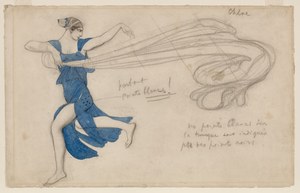

Among those who drew on classical art and motifs was the Ballets Russes’ prolific set and costume designer Léon Bakst (1866–1924). This may be seen in a watercolor of a costume that Bakst designed for Tamara Karsavina, who danced the role of Chloé in the Ballets Russes production Daphnis et Chloé. The image shows how the Greek-inspired costumes designed by Bakst gave the Ballets Russes dancer greater physical freedom and more overtly expressive gestures than traditionally dressed ballerinas. Indeed, the figure’s powerful sense of movement and her provocative dress are reminiscent of the maenad on the skyphos described above.

Inspired, in part, by ancient art and mythological figures, L’Après-midi d’un Faune (The Afternoon of a Faun) choreographed for the Ballets Russes by Vaslav Nijinsky, is a story of sexual awakening. With music by Claude Debussy and scenery and costumes by Bakst, it tells the tale of a faun who pursues a group of nymphs on their way to bathe, frightening off all but one. When she too flees, dropping her scarf, the faun, danced by Nijinsky himself, finds the scarf and uses it to mime a final sexual gesture that scandalized audiences when the ballet was first performed in Paris in 1912.

Hymn to Apollo includes a group of stunning photographs of L’Après-midi d’un Faune taken by Adolf de Meyer (1868–1946), one of the preeminent photographers of the pre-World War I Ballets Russes. Seeking to create an environment that evoked a world apart, de Meyer used his own lighting schemes, shot some images through gauze, and elaborately retouched his negatives, giving his pictures a painterly quality. Maintaining both the shallow stage space created by Bakst’s designs and Nijinsky’s two-dimensional treatment of space, the photographs, like Nijinsky’s choreography, have the look of ancient relief carving.

Léon Bakst. Costume Design for Tamara Karsavina as Chloé, for Daphnis et Chloé. ca. 1912. Graphite and tempera and/or watercolor on paper. H. 28.2 cm; W. 44.7 cm. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund: 1933.392 Image: Allen Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum

Apollo was the god of music, poetry, knowledge, and healing, and stood for order and intellectual enrichment; he was half-brother to Dionysus, who is identified with devotion to the pleasures of the body. Apollo, too, inspired Ballets Russes productions, including Apollon Musagète (1928), choreographed by a young George Balanchine (who would later revise it for New York’s City Ballet) with music by Igor Stravinsky. Rather than representing Apollo as a heroic Olympian from the very outset, the ballet followed his growth from, in Balanchine’s words, “a boy with long hair” to his ascent to the peak of Mount Parnassus. Stravinsky’s score was for strings alone, a serene and transparent orchestration that inspired Balanchine’s choreography. Apollon Musagète is illuminated through photographs, a page from Stravinsky’s hand-written score, and a digitized audio recording of the music.

Léon Bakst. Costume Design for Tamara Karsavina as Chloé, for Daphnis et Chloé. ca. 1912. Graphite and tempera and/or watercolor on paper. H. 28.2 cm; W. 44.7 cm. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund: 1933.392 Image: Allen Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum

Apollo was the god of music, poetry, knowledge, and healing, and stood for order and intellectual enrichment; he was half-brother to Dionysus, who is identified with devotion to the pleasures of the body. Apollo, too, inspired Ballets Russes productions, including Apollon Musagète (1928), choreographed by a young George Balanchine (who would later revise it for New York’s City Ballet) with music by Igor Stravinsky. Rather than representing Apollo as a heroic Olympian from the very outset, the ballet followed his growth from, in Balanchine’s words, “a boy with long hair” to his ascent to the peak of Mount Parnassus. Stravinsky’s score was for strings alone, a serene and transparent orchestration that inspired Balanchine’s choreography. Apollon Musagète is illuminated through photographs, a page from Stravinsky’s hand-written score, and a digitized audio recording of the music.

Ancient Egypt was the source for Cléopâtre (Cleopatra) (1909), a one-act ballet featuring ecstatic Dionysian movement, with choreography by Michel Fokine, scenery and costumes by Bakst, and music by a potpourri of Russian composers. Cleopatra was initially performed by the daring, strikingly beautiful, and erotic Ida Rubinstein, and Amoun by Fokine himself. Bakst’s dazzling costume for a female slave is here, a multi-colored, multi-patterned dress that contains a frieze-like design of Egyptian-style figures in profile.

Bakst’s set and many of his costumes for Cléopâtre were destroyed in a fire on one of the company’s many tours, and Diaghilev commissioned visual artists Sonia and Robert Delaunay to create new costumes and a new set. Watercolors and photographs of some of their designs show that while the artists looked to ancient Egyptian art for inspiration, their works, clearly conceived in a modernist register, straddle the line between abstract form and representation.

Bakst continued to have a working relationship with Ida Rubinstein after she left the Ballets Russes. One of their final collaborations was on Rubinstein’s production of the ballet Phèdre (1923), represented here by an array of designs including costumes and stage props such as an amphora with decorations bearing similarities to a vessel excavated from the Egyptian tomb of Sennedjem, on view nearby.

Another contemporary artist called upon to work with the Ballets Russes was Giorgio de Chirico, who designed both costumes and sets for Le Bal (The Ball) (1929), a tale of love, deception, and jealousy unfolding at a masquerade ball. While the story does not take place in ancient times, de Chirico’s designs—like his paintings—were nonetheless inspired by ancient landscapes and architectural ruins. As seen in a costume for a male guest, the artist painted architectural fragments directly onto the ensemble so that bricks, columns, and capitals come to life as the dancers move. Le Bal was Diaghilev’s final ballet before his unexpected death in 1929, but the company’s new, modern vision of the ancient world was one part of its enduring legacy in the history of dance.

Support

Hymn to Apollo: The Ancient World and the Ballets Russes and its accompanying catalogue were made possible by generous support from the Selz Foundation, The New York Community Trust—LuEsther T. Mertz Advised Fund, Anne H. Bass, the Evelyn Sharp Foundation, and the Leon Levy Foundation. Additional funding has been provided by Mr. and Mrs. Frederick W. Beinecke.