Food and Diet in Greco-Roman Antiquity

This article appeared in ISAW Newsletter 23, Winter 2019.

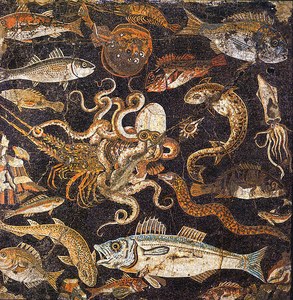

Roman mosaic from house VIII.2.16 in Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale (Naples), inv. nr. 120177

This past spring I led a group of students and scholars from ISAW and NYU Classics in a seminar considering food and diet in Greco-Roman antiquity through three different lenses: science, practice, and culture. Beginning with an overview of theories of nutrition and digestion, we discussed medical advice on regimen, a concept that in the Greco-Roman world extended beyond diet as we think of it today to include sleep, exercise, bathing, sexual habits, and even wardrobe. The Greeks in particular put a major emphasis on diet as a preventative tool, but also regarded dietetic change as a safer and gentler therapeutic alternative to the pharmacopeia. We then considered the practicalities of diet, finding that food penetrated all areas of antiquity; our readings here ranged from archaeological surveys of animal bone fragments on ancient farms to Virgilian poetry, from reconstructions of Greek religious sacrifice and Roman military diets to economic theories of supply and demand in the grain trade. Finally, we turned to the culture surrounding food. Here we saw that, like today, the ancients were acutely aware of the social and philosophical ramifications of the foods they chose to eat. Diet was a means through which to express—and be judged for—one’s wealth, status, taste, and moral convictions. As Juvenal reminds us, “you must know your own measure and keep it in sight in matters great and small, even in the business of buying fish” (Satire XI.35-38 (Braund)).

Roman mosaic from house VIII.2.16 in Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale (Naples), inv. nr. 120177

This past spring I led a group of students and scholars from ISAW and NYU Classics in a seminar considering food and diet in Greco-Roman antiquity through three different lenses: science, practice, and culture. Beginning with an overview of theories of nutrition and digestion, we discussed medical advice on regimen, a concept that in the Greco-Roman world extended beyond diet as we think of it today to include sleep, exercise, bathing, sexual habits, and even wardrobe. The Greeks in particular put a major emphasis on diet as a preventative tool, but also regarded dietetic change as a safer and gentler therapeutic alternative to the pharmacopeia. We then considered the practicalities of diet, finding that food penetrated all areas of antiquity; our readings here ranged from archaeological surveys of animal bone fragments on ancient farms to Virgilian poetry, from reconstructions of Greek religious sacrifice and Roman military diets to economic theories of supply and demand in the grain trade. Finally, we turned to the culture surrounding food. Here we saw that, like today, the ancients were acutely aware of the social and philosophical ramifications of the foods they chose to eat. Diet was a means through which to express—and be judged for—one’s wealth, status, taste, and moral convictions. As Juvenal reminds us, “you must know your own measure and keep it in sight in matters great and small, even in the business of buying fish” (Satire XI.35-38 (Braund)).