Research and Teaching on Ancient Wine

This article appeared in ISAW Newsletter 23, Winter 2019.

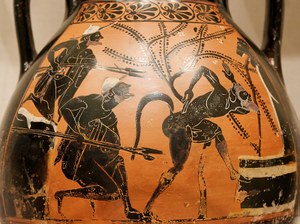

Silenus Captured Drunk by the Guards of King Midas: Black-figure Painted Wine Jar, c 510 BCE. Image courtesty of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Recent fieldwork in Cappadocia (Turkey), at the site of Kınık Höyük, uncovered unique evidence of grapevine cultivation and wine production in the first millennium BCE central Anatolia. In this region, the Neo-Hittite rock reliefs depict the Storm-god of the vineyard, holding a grapevine in one hand and an ear of wheat in the other, in place of the usual iconography of mace and thunder. This indicates that grapes and wine were key for this region in pre-classical times. ISAW PhD student Lorenzo Castellano conducted palaeobotanic analyses which prove that grapevine cultivation was widespread, becoming so intensive between ca. 500-50 BCE that the inhabitants of the site regularly used pruned grapevine branches as fuel for fires. This evidence is unique within central Anatolia; in contrast, even the floral record from Gordion, capital of ancient Phrygia, counts almost no grapevine remains in the same period.

Silenus Captured Drunk by the Guards of King Midas: Black-figure Painted Wine Jar, c 510 BCE. Image courtesty of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Recent fieldwork in Cappadocia (Turkey), at the site of Kınık Höyük, uncovered unique evidence of grapevine cultivation and wine production in the first millennium BCE central Anatolia. In this region, the Neo-Hittite rock reliefs depict the Storm-god of the vineyard, holding a grapevine in one hand and an ear of wheat in the other, in place of the usual iconography of mace and thunder. This indicates that grapes and wine were key for this region in pre-classical times. ISAW PhD student Lorenzo Castellano conducted palaeobotanic analyses which prove that grapevine cultivation was widespread, becoming so intensive between ca. 500-50 BCE that the inhabitants of the site regularly used pruned grapevine branches as fuel for fires. This evidence is unique within central Anatolia; in contrast, even the floral record from Gordion, capital of ancient Phrygia, counts almost no grapevine remains in the same period.

Since Ancient Greek poets, historians, and vase painters conceived Phrygia as the most ancient nation in the world, attributing to it nearly all pre-classical Anatolian memory, they associated Phrygia with wine cultivation, production, use, and inebriation. Thus, the Phrygian golden-touch King Midas was said to have captured half-man, half-horse Silenus by filling a spring with wine and intoxicating him in order to profit from his wine-derived, inspired wisdom.

Research on the study of ancient wine has made enormous progress in the last twenty years, identifying the area between the south Caucasus and eastern Turkey as the place of domestication of the grapevine and the first production of wine.

In an ISAW graduate course this spring, we will explore these early periods of wine production and their development in western Asia and the eastern Mediterranean. In addition to studying archaeological methodologies to investigate ancient wine and the context of its use, circulation, and storage, the course will investigate the social rituals associated with wine-drinking and how these developed from the late Neolithic down to the archaic Greek banquet (symposion). Simultaneously, the course will cover beer-drinking and its relation to the evolution of wine’s economic and cultural value in the Mediterranean.