Dispatch From the Archives

Defining the Ancient in Early Modern Europe

Frederic Clark

Visiting Assistant Professor

This article first appeared in ISAW Newsletter 16, Fall 2016.

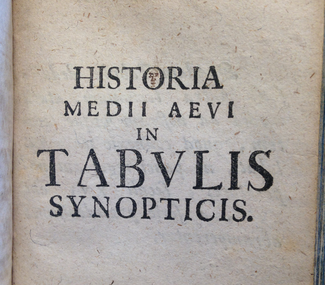

A face sketched in the “O” of Historia medii aevi or “The history of the Middle Ages”. Photo courtesy of Frederic Clark.

Thanks to the generosity of ISAW’s research support, I spent part of this summer in England, finishing up work on my book, Dividing Time: The Invention of Historical Periods in Early Modern Europe. This book explores how European scholars in the period between 1400 and 1800 began to separate historical time into ancient, medieval, and modern phases. It begins with the fourteenth-century Italian humanist Petrarch and ends with the eighteenth-century English historian Edward Gibbon. During these centuries, early modern Europeans debated when exactly the modern age had begun, and which eras counted as truly ancient. Had Rome “fallen,” and if so when and why had such a fall taken place? Was it possible, or desirable, to revive antiquity? And what purposes did a millennium-long “middle” age between ancient Rome and contemporary Europe serve?

A face sketched in the “O” of Historia medii aevi or “The history of the Middle Ages”. Photo courtesy of Frederic Clark.

Thanks to the generosity of ISAW’s research support, I spent part of this summer in England, finishing up work on my book, Dividing Time: The Invention of Historical Periods in Early Modern Europe. This book explores how European scholars in the period between 1400 and 1800 began to separate historical time into ancient, medieval, and modern phases. It begins with the fourteenth-century Italian humanist Petrarch and ends with the eighteenth-century English historian Edward Gibbon. During these centuries, early modern Europeans debated when exactly the modern age had begun, and which eras counted as truly ancient. Had Rome “fallen,” and if so when and why had such a fall taken place? Was it possible, or desirable, to revive antiquity? And what purposes did a millennium-long “middle” age between ancient Rome and contemporary Europe serve?

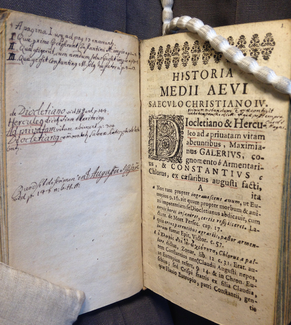

Dividing Time examines evidence of changing perceptions of the past in acts of reading, some of them performed by well-known scholars, and others by obscure or even anonymous individuals. For this reason, I spent most of my days at the British Library, tracking down marginal notes that readers entered in the copies of their books. History textbooks proved to be fruitful sources. For instance, how did students respond to key events on the seeming borderlands between antiquity and the middle Ages, from Constantine’s conversion to Christianity to Charlemagne’s coronation as emperor? Here is an example of one such response: student notes in the 17th-century German scholar Christopher Cellarius’ Universal History Divided into Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times (one of the first textbooks to use this threefold division of time in such explicit fashion).

A student’s notes in the 17th-century German scholar Christopher Cellarius’ Universal History Divided into Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times. Photo courtesy of Frederic Clark

Although this reader was an assiduous note-taker, all was not serious. I was delighted to see that they too engaged in a pedagogical practice that transcends historical periods: namely, the art of the doodle. Above is a face they sketched in the “O” of Historia medii aevi or “The history of the Middle Ages.” Dividing time required both learning and levity!

A student’s notes in the 17th-century German scholar Christopher Cellarius’ Universal History Divided into Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times. Photo courtesy of Frederic Clark

Although this reader was an assiduous note-taker, all was not serious. I was delighted to see that they too engaged in a pedagogical practice that transcends historical periods: namely, the art of the doodle. Above is a face they sketched in the “O” of Historia medii aevi or “The history of the Middle Ages.” Dividing time required both learning and levity!

I’m immensely grateful for this wonderful opportunity, and look forward to sharing the results of my research with the ISAW community this fall.