A Serendipitous Journey

My Parisian hosts had warned that a wildcat rail strike was threatened for Monday, May 14. Since April, the National Society of French Railways (SNCF) had been protesting President Emmanuel Macron’s proposed economic reforms but adhering to a calendar of strike days, announced in advance and continuing through June. I was to meet my friend Eleanor in Lille, she arriving on the Eurostar from London, I on the only train running that morning from Paris. We each had been assured that our train would run, and indeed both did: Eleanor was awaiting me on the platform.

Why this journey, carefully planned weeks before to conform to the strikers’ schedule as well as ours? Because the Musée du Louvre’s outpost in Lens, in a former coalmine yard about 125 miles north of Paris, was staging an extensive exhibit of Qajar art, its title—“L’Empire des roses,” in English, “Empire of Roses. Masterpieces of 19th-Century Persian Art.” My passion for the art of this period stems from my work on the art and archaeology of pre-Islamic Iran, specifically Achaemenid (c. 550-332 BCE) and Sasanian (224-651 CE), and the reuse of those dynasties’ visual motifs during the Qajar dynasty (1789-1925); as an historian of Islamic Persian art, Eleanor’s interests dovetail with mine.

But we had not taken into account that getting to Lens required another train, impossible that day. What to do? Lille’s Palais des Beaux Arts beckoned, but our eyes fell on a notice in the Eurostar magazine: an exhibition of East Christian art (“Chrétiens d’Orient—2000 ans d’histoire”) in Tourcoing, a medieval town on the Belgian border, largely destroyed and rebuilt after each World War, once a major textile center and now absorbed by Lille. The Lille Métro took us there in 30-minutes.

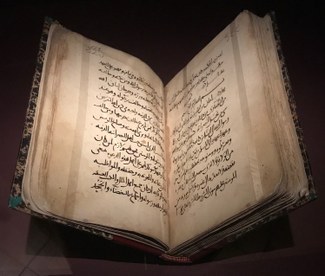

The Chronicle of Seert. An ecclesiastical history written in Arabic by an anonymous Nestorian Christian writer. This volume was written in the 11th century in Mosul, northern Iraq.

(Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Ms. Arabe 6653).

Anticipating a small exhibition with enough time to return to Lille and visit its museum, we entered Tourcoing’s 19th-century Musée des Beaux-Arts around one and did not leave until they closed its doors four hours later. Based on a previous exhibition at the Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, this extraordinarily rich and moving display of the religious, political, cultural and art history of Christianity as it has been practiced across the Middle East, from Egypt to Iraq and to Armenia, was all the more poignant for it contained several objects only recently saved from destruction in this turbulent region.

Fragment of a plate showing the Descent from the Cross, Syria, end of 13th-first half of 14th century. (Athens, Benaki Museum, E 823).

For us, Tourcoing was truly “Serendipity,” a word coined by Horace Walpole, inspired by the 16th-century tale, The Three Princes of Serendip, in which the three, as they travelled, “were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of” (letter of January 28, 1754). Fittingly, the tale is an adaptation from the 14th-century Persian poem, Hasht-Behesht, itself an adaptation of the life of the Sasanian king, Bahram V (r. 420-440 CE).

For us, Tourcoing was truly “Serendipity,” a word coined by Horace Walpole, inspired by the 16th-century tale, The Three Princes of Serendip, in which the three, as they travelled, “were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of” (letter of January 28, 1754). Fittingly, the tale is an adaptation from the 14th-century Persian poem, Hasht-Behesht, itself an adaptation of the life of the Sasanian king, Bahram V (r. 420-440 CE).

“L’Empire des roses” continues until 23 July: another reason to return to Paris and from thence to Lille, but this time I will plan for a two-day stay to see Lille’s own art collections.