A Dialogue with the Past

When Jennifer Y. Chi, ISAW’s exhibition director, invited me to join her team for “Eye of the Shah: Qajar Court Photography and the Persian Past” and curate a gallery devoted to “the Persian Past,” I readily accepted. This was an opportunity to tell the story visually, mostly through exquisite 19th-century photographs, of a phenomenon that I’d been studying and writing about for many years: Persia’s rediscovery of its ancient past. As a historian of the art of pre-Islamic Iran—mainly that of the Achaemenid (550-330 BCE) and Sasanian (242-651 CE) dynasties—I had become interested in Qajar art back in the 1970s when I lived in Shiraz, Iran, and encountered almost daily the artistic remnants of this Turcoman dynasty that ruled from 1789 to 1925.

Qajar monumental rock reliefs and smaller reliefs of stone or plaster as architectural decoration had not been researched to any extent and I began to write about them. Of particular interest were those carved into living rock, an ancient Iranian medium of royal display, dormant for a millennium until revived by the second Qajar ruler, Fath ‘Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834). In style and iconography these reliefs borrowed from those of the Sasanian shahs who earlier had immortalized their divine investitures and military triumphs in living rock, mainly in the vicinity of Shiraz. With this shah’s death, rock relief as an expression of royal glorification reappeared only once, in 1878, under Naser al-Din Shah Qajar—the shah whose “eye” for photography (his own and others’) is the basis of the exhibition.

Relief of Fath ‘Ali Shah (1797-1834), Shiraz, Iran (J. A. Lerner)

In the latter half of the 19th century smaller-scale reliefs in stone and stucco appeared on houses in Shiraz and, to a lesser extent, in other cities. Their imagery borrows from the palatial site of Persepolis, known to Persians as Takht-e Jamshid (“the Throne of Jamshid”), situated less than 40 miles northeast of Shiraz. Sasanian motifs from the rock reliefs also occur, but most is Persepolitan: the king enthroned; the royal hero combatting mythological monsters; guards and servants.

Royal hero combatting horned lion-griffin in doorjamb of the Hundred Column, Hall, Persepolis. “Bassi-relievi a Persepolis,” from Album fotografico della Persia. Albumen print, 1857. Luigi Pesce. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2012.R.18, no. 33)

Persians had always been aware of these ancient monuments—of Persepolis (Parsa to the Achaemenids) and others, but they had lost all knowledge of who had built them. Instead, they imbued these haunting remains with the aura of the heroes and kings of the Persian national epic, the Shahnama (“Book of Kings”), composed from earlier mythic-historical accounts around the turn of the 11th century by the poet, Ferdowsi.

Then, in 1846, the English military officer and linguist, Henry C. Rawlinson (1810-1895) published his reading of the Old Persian cuneiform version of Darius the Great’s trilingual inscription carved on Bisitun mountain in northeastern Iran. He cannily presented a New Persian translation to the reigning monarch, Muhammad Shah, who ordered copies made for the royal library. With this came Persians’ growing awareness of a pre-Islamic history that ever since late Sasanian times was obscured by myth and legend. Now they learned that almost a millennium before the Sasanians, the Achaemenids had challenged the West and controlled a territory extending from the lands of the contemporary Ottoman Empire to British India. With Qajar Iran straining to counter the imperial designs of Britain and Russia, this knowledge became a source of national pride. It also fed into a nascent nationalism, as young Persians returned from studying in Europe and the many Europeans the Shah invited to modernize Persia introduced western ideas.

Achaemenid guard and royal hero combatting monster, Narangestan, Shiraz; 1880s (J. A. Lerner)

This is the background against which the 19th-century photographs of Achaemenid and Sasanian sites in Gallery One should be viewed. Rawlinson’s Bisitun reading and the accession of Muhammad Shah’s successor Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896) represents an auspicious synchronicity: Persians’ growing interest in their pre-Islamic past and the young shah’s passion for history and photography. An accomplished photographer himself, Nasir al-Din Shah encouraged the photographic recording of Achaemenid and Sasanian sites; on his travels through the country, his retinue always contained at least one photographer; he was first to use photography to record an archaeological excavation—in 1859 at the Seleucid-Parthian site of Khurha.

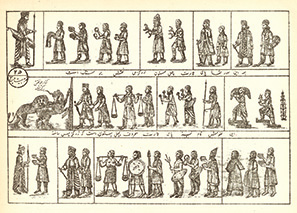

Persepolis figures, drawn by Forsat al-Dowleh,

from Asar-e ‘Ajam, Bombay, 1896

This exhibition has enabled the display of the earliest photographs of Persepolis—those of Luigi Pesce (1818–1891), a Neapolitan military advisor and accomplished amateur photographer, in the album he gifted to Rawlinson (1860)—along with magnificent views of Persepolis and other sites by the Georgian-Armenian Antoin Sevrugin (active 1870s-1933); Rawlinson’s publication of the Bisitun inscription; and the impact of the new-found knowledge of the Persian past on later 19th-century Qajar art, exemplified by an alabaster relief in Persepolitan style, photographs of a Qajar townhouse embellished with Persepolitan reliefs, and pages from the polymath Forsat al-Dowla Shirazi’s Asar-e ‘Ajam (“Persian Monuments“; 1896), with its accurate renditions—albeit in the distinctive Qajar style—of the reliefs and buildings at Persepolis.

Before “Eye of the Shah” opened, some had wondered why an exhibition of 19th-century Persian photography was at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. As I have shown, it is appropriate to ISAW’s mission encouraging study of “historical connections and patterns, as well as socially illuminating comparisons.” “Eye of the Shah” reveals the dialogue between the ancient past—pre-Islamic Iran—and the more recent present—Qajar Persia in the second half of the 19th century.