Tales from the Alexander Romance in "Romance and Reason: Islamic Transformations of the Classical Past"

Romance and Reason: Islamic Transformations of the Classical Past explores how images and stories from Classical antiquity were incorporated into Islamic culture in manuscripts from the 11th through 18th centuries. One fascinating case is the transformation of Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) and ISAW is currently showing works representing the Persian and Turkish versions of the legendary account of Alexander the Great, or Iskandar, as he is known in the Islamic tradition. Muslim fascination with this Macedonian conqueror emerged from a cryptic reference in the Qur’an and early Islamic exegesis, as well as widely circulating tales about Alexander’s exploits in Greek, Syriac, Hebrew, Persian, and other cultures and traditions. In a number of works now on view in our galleries, Alexander is represented with horns.

The historian Arrian of Nicomedia (ca. 86–160 CE) describes Alexander’s trip through the Libyan desert, to the oasis of Siwa, to consult the oracle of Ammon. Ammon, a Libyan divinity, was frequently represented with ram’s horns and entered the Egyptian pantheon as the god Amun. While the question Alexander posed to the deity is unknown, Arrian reports that he received “the answer that his heart desired.” Following this auspicious encounter, Alexander began representing himself as the son of Ammon and depictions of him with ram’s horns, in tribute to the oracle, appear on coins, in statuettes, and busts.

The tale of Alexander’s encounter with Ammon is an episode included in the Alexander Romance—Greek stories recounting the mythical adventures of Alexander the Great—and the tradition of his representation with horns continued in the Islamic world. Chapter eighteen of the Qur’an (Surat al-Kahf [the Cave]) references a figure known as “The Two-Horned One,” or in Arabic, dhu al-qarnayn. This story tells of a figure that traveled east and west, meet different peoples, and built fortifications to protect against Gog and Magog. Most commentators have identified “The Two-Horned One” as Alexander the Great, but not every scholar has agreed. The Muslim historian and exegete al-Tabari (839–923 CE) interpreted the name differently and wrote that dhu al-qarnayn is a reference to Alexander’s conquest of East and West, the two “horns” of the world.

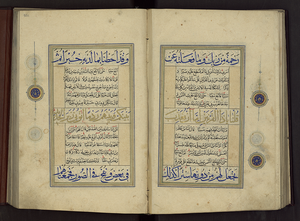

Qur᾿an

Folios 200 verso, 201 recto: Qur᾿an Verse Referring to “The Two-Horned One”

(Surat al-Kahf [The Cave], 18:86)

Copyist: Unknown; Language: Arabic, with Persian prayers in appendix

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Iran, early 16th century

From the collections of The National Library of Israel: Ms. Yah. Ar. 910

The Qur’an includes only sixteen verses of the story of “The Two-Horned One,” but other Muslim exegetical literature expands upon this reference. Commentators such as Tabari, Thalabi (d. 1035), and others collected tales of pre-Islamic prophets that circulated widely in early Muslim literature. In these stories, Alexander is transformed from conqueror to mystical seeker and faithful prophet.

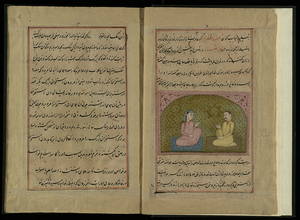

The Story of Iskandar, The Two-Horned One (Qissah-yi Iskandar Dhu al-Qarnayn)

Folio 3 recto: Iskandar as The Two-Horned One Discusses the Coming of the Prophet Muhammad

Author: Unknown; Copyist: Unknown; Language: Persian

Ink and opaque watercolor on paper

Iran-India, 18th century

From the collections of The National Library of Israel: Ms. Yah. Ar. 1060

The Story of Iskandar, The Two-Horned One, a late Persian prose text, drew on the Qur᾿anic story and its interpretive tradition, together with the Persian epics, and popular folktales. In this later version, Iskandar is depicted as having actual horns.

Romance and Reason: Islamic Transformations of the Classical Past is on view through May 13, 2018. We look forward to welcoming you in our galleries!