Austen Henry Layard and the early exploration of Nimrud

Last month, The Islamic State of Syria and the Levant issued a video depicting the vandalizing of the ancient Assyrian city of Kalhu, better known as Nimrud. The IS claims to have vandalized sculptures and bulldozed structures prior to the detonation of heavy explosives in the vicinity of the city's palaces. This is the latest in a series of such events, including the destruction of antiquities in the Mosul Museum, damage to the Hatra site, and the destruction of numerous Shi’ite shrines in Mosul. The IS has made grandiose claims about the extent of the destruction, but there has been virtually no outside confirmation of how much damage has actually been done at Nimrud. Nevertheless, the possibilities are troubling.

Fortunately, the palace district of Nimrud/Kalhu is one of the better-explored Assyrian sites, largely due to the publications issued following the site’s initial excavation, many of which are held by the ISAW Library. The first excavation at Nimrud was undertaken in 1845 by a French-born Englishman named Austen Henry Layard.[1] Layard, whose uncle had achieved some success in Ceylon, began a lengthy sojourn in the Near East in 1839. He set out from London intending to travel by land to Ceylon to secure a Civil Service appointment, hoping perhaps to follow in his uncle’s footsteps. But he soon fell in love with travel itself, and spent the next several years wandering in Persia, Asia Minor, and the Middle East. He was briefly appointed as a secretary to Sir Stratford Canning in Constantinople before departing for Iraq in 1845 to search for Assyrian antiquities. He was initially invited by French archaeologist Paul-Émile Botta to join his excavation of the Kouyunjik Mound, on the opposite bank of the Tigris from Mosul. But, concerned about the watchful eyes of the people of the city, he instead selected a site some twenty miles south: the city of Nimrud.

The Kalhu site, dominated by a 140-foot conical mound containing the remains of a large ziggurat, was known to Layard from his previous travels in the region. The city was called Calah in Genesis, and its ruins were described by Xenophon, who called it Larisa. The site was named “Nimrud” in later years, owing to local tradition that connected the city to the Biblical figure Nimrod (who is named alongside with the city in Gen 10:8-12). The city fell to the Babylonians in about 612 B.C.E., and was abandoned. The site was described but not excavated by Claudius Rich in 1820, and Layard was the first to explore the ruins systematically.

The local Ottoman rulers posed problems for Layard, particularly Mohamed Pasha, the tyrannical Ottoman governor of Mosul, and the kadı of Mosul, an Ottoman official who believed Layard wished to send the Assyrian sculptures “to the palace of your Queen, who, with the rest of the unbelievers, worships these idols.”[2] There was some concern that any sculptures discovered would be destroyed as blasphemous idols, as had happened to a sculpture uncovered at Koyunjik by Claudius Rich in 1820. Other locals were certain that Layard had information regarding the location of gold inside the mounds, while some believed that European archaeologists were searching for proof that the territory had once been held by the Franks, in order to justify the colonial seizure of the region. Layard needed to repeatedly re-secure his permission to excavate.

Layard’s excavations at Nimrud were fruitful. His primary goal was the discovery of Assyrian sculpture, and this the site provided in great abundance. Layard’s contemporaries had different ideas about the relative importance of artwork and inscriptions. Biographer Gordon Waterfield writes:

[Henry] Rawlinson argued that [inscriptions] would be of infinitely greater value than bas-reliefs, for he was certain that very soon he would be able to decipher them completely but Layard realised that it had been the Khorsabad bas-reliefs which had aroused the interest of Europe and that urgently needed funds would not be raised for the finding of cuneiform inscriptions which might take many years to decipher. Stratford Canning agreed with this, for people, he said, resembled children in that ‘they like to look at the pictures.’[3]

Layard shipped the majority of his finds to London, where they came to form the core of the British Museum’s collection of Assyrian antiquities. Among the major finds from the expedition were two colossal winged lions, which Layard insisted be kept intact, unlike similar lamassu from Khorsabad that had been cut into smaller sections for their transportation to the Louvre Museum. Layard moved his winged lions whole, much in the same way they had originally been transported to Nimrud in antiquity.

Layard’s work in Nimrud and Nineveh was the cause of much excitement in England. To his frustration, his associates had published some of his letters in the London press, and the pressure was on for him to publish a full account of his discoveries. Echoing Stratford Canning’s comments on the public’s desire for pretty pictures, Layard’s friend Charles Alison encouraged him to “Write a whopper with lots of plates… Fish up old legends and anecdotes, and if you can by any means humbug people into the belief that you have established any points in the Bible, you are a made man.”[4]

Layard quickly assembled a lengthy two-volume account of his travels in Iraq, published by John Murray in 1848-1849 with the title Nineveh and Its Remains. (Though the work also discusses the Kouyunjik site, the book is primarily about the Nimrud excavations. The title is based on Rawlinson’s theory that the Nimrud site was in fact Nineveh. The true location of Nineveh opposite Mosul was definitively established shortly after this publication.) Nineveh and Its Remains was an immediate bestseller. In addition to a detailed account of the excavation and discoveries, Layard’s text is a lively travel narrative, filled with details of local life and customs, political intrigue between Ottoman rulers and Arab tribesmen, and observations on the situation of religious minorities in Iraq and Persia.

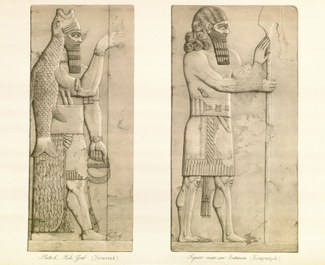

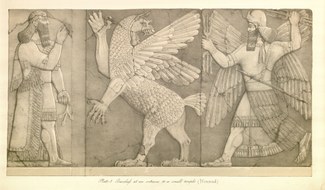

The two-volume book was accompanied by a lavish folio volume of plates, entitled Monuments of Nineveh. Containing 100 highly-rendered engravings and lithographs, the work is an indispensable guide to the materials unearthed during Layard's initial excavations at Nimrud and Nineveh. Many of the sculptures and bas-reliefs pictured in the volume were either too fragile to remove or were damaged following their excavation, leaving these plates as the best available record of their condition and contents. The text of the colorful title page is printed in an orientalist mock-cuneiform style. Monuments of Nineveh was sold by subscription, and the subscribers are listed at the beginning of the volume. Among them are Queen Victoria and her mother, Sir Stratford Canning, diplomat Robert Curzon, and the British East India Company.

Layard undertook a second expedition in 1849, this time focusing on the Koyunjik Mound (the actual site of Nineveh) and Babylon, with brief visits to numerous other sites. One major find from this second expedition was the Library of Ashurbanipal, consisting of some 25,000 cuneiform tablets and containing the most complete known texts of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Of these tablets, Layard—writing before the contents of the find had been fully examined—stated: “We cannot overrate their value. They furnish us with materials for the complete decipherment of the cuneiform character, for restoring the language and history of Assyria, and for inquiring into the customs, sciences, and, we may perhaps even add, literature, of its people.”[5]

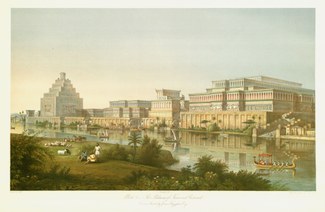

Layard’s second trip resulted in another two-volume work, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, and a second volume of plates, A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh. This volume focused largely on bas-reliefs and sculptures from the palace of Sennacherib in the Kouyunjik site. (With this work, Layard adopted the dominant position regarding the location of Nineveh, albeit without comment on the previous book’s identification of Nimrud as Nineveh). Of the bas-reliefs, Layard writes in the introduction: “Some are of the highest interest, as illustrative of events mentioned in Holy Writ."[6] The frontispiece of the collection is a full-color lithograph imagining the appearance of Nimrud at its apex, with a brightly-colored ziggurat and palaces, active river traffic on the Tigris, and idling shepherds in the foreground.

Following his second excavation of Assyrian sites, Layard entered politics, and spent many years as the British Ambassador at Constantinople. An additional publication of his finds was published in 1851: Inscriptions in the Cuneiform Character from Assyrian Monuments. Though he contributed some initial editorial work, Layard seems to have had little involvement with the final publication. The volume is one of the first volumes to be printed in a cuneiform typeface, using a font that seems to have been custom-made for the publication by London printers Harrison and Son.[7] In his retirement, Layard authored a book detailing his early travels in the Near East, prior to his archaeological expeditions, entitled Early adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia, which was published in 1887, and reissued in an abridged edition after his death in 1894.

The ISAW Library holds early editions of all of Layard’s major works, many of them from the library of Hayim and Miriam Tadmor. Among these is a complete set of the two-volume folio Monuments of Nineveh, containing detailed engravings of bas-reliefs, sculptures, and inscriptions from Nimrud and Nineveh. The library also holds many additional works on the Nimrud site, several of which can be found in the primary call number range for the Kalhu site (DS70.5.C3). More may be discovered by a Bobcat search for the Library of Congress subject heading “Calah (Extinct city).”

The destruction at Kalhu is a tragedy, but there is some consolation in the fact that the finds from the site were thoroughly published from the time of their discovery. In a post on the IS's campaign against antiquities, Christopher Jones states: "Our best weapon against the erasure of history remains documentation and publishing." For Nimrud, Layard's works inaugurated a long legacy of documentation that will survive in perpetuity.

Selected works by and about Austen Henry Layard in the ISAW Library

Nineveh and Its Remains. 5th edition. London: John Murray, 1850. 2 volumes. From the Library of Hayim and Miriam Tadmor. ISAW Antiquarian Collection DS70.L34 1850.

The Monuments of Nineveh. London: John Murray, 1849. From the Library of Hayim and Miriam Tadmor. ISAW Antiquarian Collection N5380.L3 1849 Folio.

Inscriptions in the Cuneiform Character from Assyrian Monuments. London: Printed by Harrison and Son; Sold at the British Museum, 1851. From the Library of Hayim and Miriam Tadmor. ISAW Antiquarian Collection PJ3711 .B725 1851 Folio.

Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. London: John Murray, 1853. 2 volumes. From the Library of Hayim and Miriam Tadmor. ISAW Antiquarian Collection DS70 .L33 1853 pt.1 & 2. Also another edition: New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1853. A Gift from Cornelius and Emily Vermeule. ISAW Antiquarian Collection DS70.L33 1853a.

A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh. London: John Murray, 1853. From the Library of Hayim and Miriam Tadmor. ISAW Antiquarian Collection N5380.L3 1853 Folio.

Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia. New edition. London : John Murray, 1894. From the Library of Hayim and Miriam Tadmor. ISAW Small Collection DS48.5 .L4 1894.

Gordon Waterfield. Layard of Nineveh. London: John Murray, 1963. ISAW Small Collection DS70.88.L3 W3 1963.

[1] For the biographical material on Layard, this post is indebted to Gordon Waterfield, Layard of Nineveh. London: John Murray, 1963. ISAW Small Collection DS70.88.L3 W3 1963.

[2] Austen Henry Layard. Nineveh and its remains. 5th ed. London: John Murray, 1850, vol. 2, p. 84. ISAW Antiquarian Collection DS70.L34 1850.

[3] Waterfield, pp. 122-123.

[4] Quoted in Waterfield, p. 171.

[5] Austen Henry Layard. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. London: John Murray, 1853, vol. 2, p. 347. ISAW Antiquarian Collection DS70.L33 1853.

[6] Austen Henry Layard. A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh. London: John Murray, 1853, p. [v]. ISAW Antiquarian Collection N5380.L3 1853 Folio.

[7] According to Waterfield (p. 180), Botta had offered Layard the use of the custom cuneiform font created for his Monument de Ninive, but a different type was ultimately used for the British Museum publication. Harrison and Son presented their cuneiform typeface in 1851 at the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace in London. Cf. David M. MacMillan and Rollande Krandall, “[UK] Harrison and Son.” Circuitous Root. MacMillan and Krandall, 2011.