“Forgotten lore”: Poe’s antiquity

September has been an exciting month for me: two weeks ago I officially joined the staff of the ISAW library, and that same week also saw the opening of an exhibition I co-curated for the Grolier Club. “Evermore: The Persistence of Poe” (on view through November 22) illustrates the life, work, and literary afterlife of Edgar Allan Poe, drawing on the formidable collection of Susan Jaffe Tane, who holds the foremost privately-owned collection of Poe in the world. Though the exhibit is thoroughly rooted in 19th century America—with forays into Poe’s reception overseas and his ongoing influence on 150 years of American popular culture—it also illustrates Poe's strong interest in ancient subjects. Though it’s not unusual to think of Poe as an author who dwelt in the past, we tend to associate him with gothic castles—or Renaissance wine cellars. Some of his best-remembered tales of terror, including "The Black Cat" and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” are set in contemporary urban America. But Poe based many stories in ancient settings, as well.

Poe's knowledge of classics was deep. He enrolled in the University of Virginia in 1826, a member of one of the school’s first classes. There, he primarily studied ancient and modern languages. In his studies of Greek and Latin (in which he particularly excelled), he was called upon to read, memorize, and translate the works of Virgil, Thucydides, and Horace, among others. Poe also excelled at French, which he also used to expand his knowledge of the ancient world: library records indicate that he read Charles Rollin’s Histoire Ancienne and Histoire Romaine. Poe departed the University of Virginia after a single rocky year, but he remained a voracious reader throughout his life. Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, / Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore ...

Poe’s knowledge of the ancient world turns up in several of his tales and poems. “Some Words With a Mummy” is a comic tale about the then-newly popular field of Egyptology in which a revived inhabitant of Egypt skewers the American exceptionalism of his discoverers. The poem “The Coliseum” is a Byronic ode to the ruins of past grandeur.

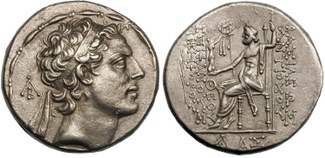

But among the most interesting examples of Poe’s use of ancient settings is the tale “Epimanes,” the manuscript of which is on display in the exhib ition at the Grolier Club. The brief tale—also published under the title “Four Beasts in One; the Homo-Cameleopoard”—is set in Antioch during the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes ("God Manifest"), who seized the Seleucid throne in 175 BCE. Though not the cruelest monarch of his era, he became chief villain of the books of Maccabees, and his conduct led the Greek historian Polybius, his older contemporary, to dub him “Epimanes” (“madman”).

ition at the Grolier Club. The brief tale—also published under the title “Four Beasts in One; the Homo-Cameleopoard”—is set in Antioch during the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes ("God Manifest"), who seized the Seleucid throne in 175 BCE. Though not the cruelest monarch of his era, he became chief villain of the books of Maccabees, and his conduct led the Greek historian Polybius, his older contemporary, to dub him “Epimanes” (“madman”).

In the tale “Epimanes,” Poe depicts a mad revel commemorating the execution of a group of Jewish prisoners. The celebration involves a procession of wild beasts, a Latin hymn in celebration of bloodshed, and the King himself cavorting in imitation of a giraffe. It is a strange tale, to be sure, but not without a certain power, particularly in Poe’s description of the city of Antioch. He focuses not on fine architecture, but rather on the city’s “infinity of mud huts, and abominable hovels.” Poe is attracted to the dirt, dust, blood, and spectacle of ancient history. Here the term “Epimanes” describes not only the king himself, but also the mob which at first follows, and then pursues him. For Poe, the historical setting is an opportunity to explore the madness of crowds. Like the dank brownstone basement of “The Black Cat,” the crowded Parisian streets of “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” or the gloomy boarding-house of “The Tell-Tale Heart,” the streets of ancient Antioch are a setting to explore what truly interested Poe: the human mind.