Faculty Focus: Robert Hoyland

Teaching the Language of Ancient Sheba in Manhattan

The kingdoms of south Arabia tend to get overlooked in surveys of the ancient world, and yet by 800 BCE they could boast of grand temples, ornate palaces, extensive hydraulic installations and rich traditions of stone-carving, metal-working and jewelry-making. A key source of funding for all these expensive pursuits was the frankincense resin that oozed from trees native to south Arabia and that fetched high prices among the elite of Israel, Assyria and Iran. This has left its mark in the archaeological record in the form of incense altars and their paraphernalia and in the literary record in the form of fabulous tales of a blessed land of incense trees protected by “winged serpents” (Herodotus) and beautiful queens bearing aromatics (I Kings 10 on the Queen of Sheba/Saba). One might think that many scholars would be drawn to the study of such an enchanting region, but there is a major hurdle, namely its languages.

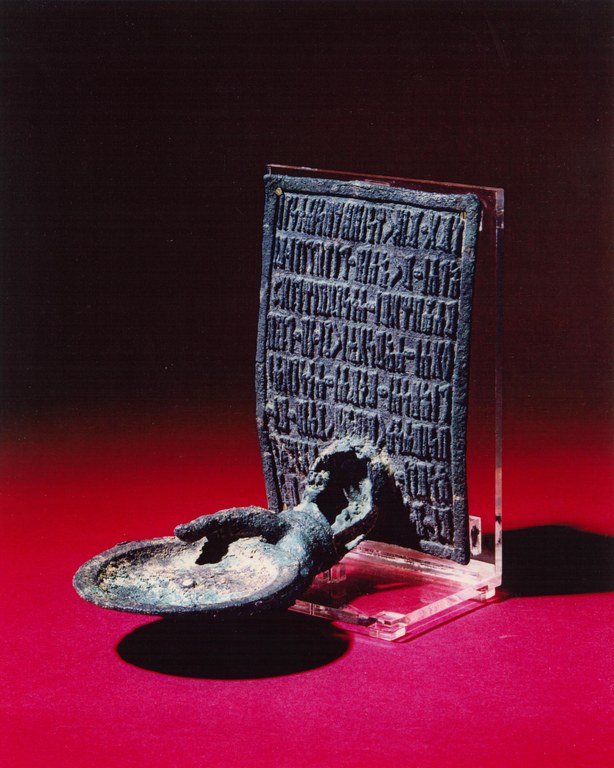

Bronze votive plaque from Timna with oil lamp held by a hand, dedicated by Hamati‘amm Dhirhan to ‘his god and lord, the master of Yaghil’, c.1st century BCE, 20 × 11.6 cm (AFSM).

First, they are not written in the 22-letter alphabet used by the Phoenicians, Hebrews, Greeks and Romans that we all know, but rather in their own 29-letter alphabet, which branched off from the proto-Sinaitic/Canaanite alphabet around 1300 BCE. Second, the relative isolation of south Arabia, some 1,300 miles – as the crow flies, let alone as the camel trots – from the main cities of the Fertile Crescent, like Jerusalem, Damascus and Seleucia-Ctesiphon, or the ports of Gaza and Charax, meant that the languages of these kingdoms are quite distinct within the Semitic family. Reading the texts produced by these ancient kingdoms is therefore no easy task and requires perseverance.

Bronze votive plaque from Timna with oil lamp held by a hand, dedicated by Hamati‘amm Dhirhan to ‘his god and lord, the master of Yaghil’, c.1st century BCE, 20 × 11.6 cm (AFSM).

First, they are not written in the 22-letter alphabet used by the Phoenicians, Hebrews, Greeks and Romans that we all know, but rather in their own 29-letter alphabet, which branched off from the proto-Sinaitic/Canaanite alphabet around 1300 BCE. Second, the relative isolation of south Arabia, some 1,300 miles – as the crow flies, let alone as the camel trots – from the main cities of the Fertile Crescent, like Jerusalem, Damascus and Seleucia-Ctesiphon, or the ports of Gaza and Charax, meant that the languages of these kingdoms are quite distinct within the Semitic family. Reading the texts produced by these ancient kingdoms is therefore no easy task and requires perseverance.

Consequently, I was both surprised and delighted when Professor Daniel Fleming of NYU’s Hebrew and Judaic Studies Department asked if I would be willing to offer an accredited course on south Arabian languages and cultures, especially as this subject has almost never been taught in America in recent decades. After an initial crash course in the basics of the grammar of ASA (Ancient South Arabian), we read a variety of texts, which survive on both hard media – stone and metal – and soft media – principally palm sticks – and which have been produced over a period of around 1500 years (ca 900 BCE – 560 CE). Some 15,000 ASA texts are known and they cover a wide range of types – prayers, hymns, dedications, legal documents – and topics – boasts of victory in war, thanks for safe passage, pleas for forgiveness, and the like. One area of research focus was the subject of oracles, which is a loose term for communication with deities, in particular involving a divine response to human questions. We are fortunate in having examples of this genre of text on both palm sticks and stone, many of them dealing with such personal problems as sickness and childbirth, but occasionally asking exciting questions like who was responsible for a murder. One of the students emphasized in the conclusion to their final paper that these ASA texts are important for a broader understanding of the ancient Middle East, and with this sentiment, I heartily agree.