Reading Greek Astronomical Inscriptions

Historians speak of the "epigraphic habit" of the Greco-Roman world, the widespread practice of inscribing texts on stone and other hard media and displaying them in public and private settings, so perhaps one should not be too surprised that there existed a tradition of making inscriptions in ancient Greek relating to astronomy. I am especially interested in astronomical inscriptions from the Hellenistic period (roughly 330 through 30 bce). By this time, knowledge of the heavenly bodies had become an area of specialist expertise, and Greek astronomy was beginning to absorb and adapt concepts and methods from Babylonia and Egypt on a large scale. Self-standing inscriptions as well as texts on sundials and other instruments are especially valuable as reflections of how astronomers engaged with the societies in which they lived.

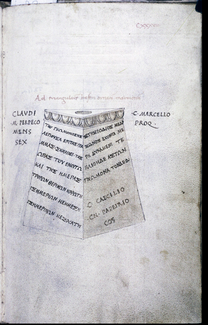

Figure 1: Copy of Cyriacus's Drawing

The starting point for studying the inscriptions is, obviously, finding out what they say: the actual words and numbers along with their layout on the physical object. In many instances this is not a straightforward matter of inspecting the object in person. Sometimes the inscription no longer exists or cannot be located. Thus on a visit to the island of Samothrace in 1444, the Italian Cyriacus of Ancona saw what must have been a pedestal for an ancient sundial, inscribed with an explanation of how to read the time and date off the dial; the stone subsequently disappeared (Figure 1). All that we have now are later copies of Cyriacus's drawing, which have mistakes in the Greek and do not even agree about whether the pedestal was square or triangular. Other vanishing acts were more recent. In 1899 German archaeologists excavating Miletus in Turkey found a fragment of inscription in a field wall, which contained dates of summer solstices in 432 and 109 bce and had something to do with regulating a lunar calendar. The text was published, but with no photograph, and although the stone was transported to Berlin in the early 20th century, it cannot be found now. Luckily I was able to locate a "squeeze" (a negative impression made in moistened paper). Then to my great astonishment I chanced upon a photograph of a second piece belonging to the same inscription among a batch of note files of the historian of science Otto Neugebauer (1899–1990) that are now in the University of Michigan's papyrology collection. This fragment had never even been mentioned in print, and but for that photo would have been lost to scholarship, depriving us of a precious witness to ancient time management.

Figure 1: Copy of Cyriacus's Drawing

The starting point for studying the inscriptions is, obviously, finding out what they say: the actual words and numbers along with their layout on the physical object. In many instances this is not a straightforward matter of inspecting the object in person. Sometimes the inscription no longer exists or cannot be located. Thus on a visit to the island of Samothrace in 1444, the Italian Cyriacus of Ancona saw what must have been a pedestal for an ancient sundial, inscribed with an explanation of how to read the time and date off the dial; the stone subsequently disappeared (Figure 1). All that we have now are later copies of Cyriacus's drawing, which have mistakes in the Greek and do not even agree about whether the pedestal was square or triangular. Other vanishing acts were more recent. In 1899 German archaeologists excavating Miletus in Turkey found a fragment of inscription in a field wall, which contained dates of summer solstices in 432 and 109 bce and had something to do with regulating a lunar calendar. The text was published, but with no photograph, and although the stone was transported to Berlin in the early 20th century, it cannot be found now. Luckily I was able to locate a "squeeze" (a negative impression made in moistened paper). Then to my great astonishment I chanced upon a photograph of a second piece belonging to the same inscription among a batch of note files of the historian of science Otto Neugebauer (1899–1990) that are now in the University of Michigan's papyrology collection. This fragment had never even been mentioned in print, and but for that photo would have been lost to scholarship, depriving us of a precious witness to ancient time management.

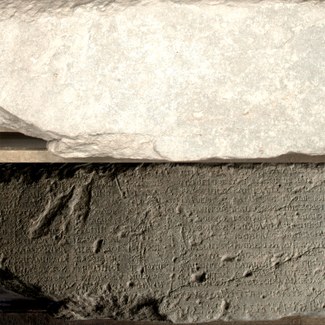

Figure 2: Two images of an astronomical inscription from Keskintos, Rhodes

Figure 2: Two images of an astronomical inscription from Keskintos, Rhodes

What if an original inscription is accessible, but so worn as to be partly unreadable? A block of stone bearing an extremely weathered list of strange, huge numbers associated with the planets turned up in 1893 on an agricultural estate on Rhodes, and is now in the Antiquities Collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. The original, century-old publication was unsatisfactory, and despite my best efforts with a flashlight in the catacombal basement of the Pergamonmuseum there remained frustrating uncertainties about some readings. Then George Bevan and Daryn Lehoux of Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario imaged the inscription using a recently invented technique called Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI - See Figure 2). RTI generates from a large set of photographs taken from a single camera position but with varying lighting direction a digital file that can be visualized to simulate alterations in the way the object's surface reflects light, bringing out surface details that are difficult or impossible to see otherwise. With the RTI files, George, Daryn, and I were able to read the last recalcitrant traces of writing; one unexpected outcome is that this technical inscription of planetary astronomy was a votive offering "to the nymphs," probably erected close by some rural spring.

Illustration Details:

Figure 1: Copy of Cyriacus's drawing of the inscribed base of an ancient sundial on Samothrace, c. 1475, Bodleian MS. lat. misc. d. 85, f. 137r.

Figure 2: Two images of an astronomical inscription from Keskintos, Rhodes: direct light (above) and RTI (below)