Nessana and its Papyri

This article first appeared in ISAW Newsletter 17, Winter 2017.

Robert Hoyland

Professor of Late Antique and Early Islamic Middle Eastern History

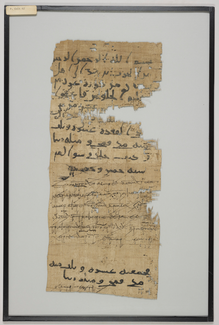

P.Nessana 62: a requisition notice in Greek and Arabic for supplies presented to the people of Nessana by the Arab governor al-Harith ibn ‘Abd in the year 55 AH (675 CE). Photo courtesy of the Morgan Library and Museum

In 1935 Harris Dunscombe Colt, son of a wealthy New York lawyer, began excavations at the small town of Nessana (modern Auja’ al-Hafir) in the Negev Desert in southern Israel with the support of New York University. He had worked with celebrated archaeologists such as Flinders Petrie in famous sites like Lachish, so it seemed to many strange that Colt would select for his own investigation a patently minor settlement in a relatively out-of-the way place. Yet it proved to be a serendipitous choice.

P.Nessana 62: a requisition notice in Greek and Arabic for supplies presented to the people of Nessana by the Arab governor al-Harith ibn ‘Abd in the year 55 AH (675 CE). Photo courtesy of the Morgan Library and Museum

In 1935 Harris Dunscombe Colt, son of a wealthy New York lawyer, began excavations at the small town of Nessana (modern Auja’ al-Hafir) in the Negev Desert in southern Israel with the support of New York University. He had worked with celebrated archaeologists such as Flinders Petrie in famous sites like Lachish, so it seemed to many strange that Colt would select for his own investigation a patently minor settlement in a relatively out-of-the way place. Yet it proved to be a serendipitous choice.

In the season of 1937 Colt’s team chanced upon a cache of some 200 papyri in one of the village’s churches, the first such find from the territory of what was Roman Palestine. It turned out to shed fascinating light on the people of this rural settlement during the sixth and seventh centuries AD and their relations with the wider world around them. The papyri concern different social groups (soldiers, farmers, clerics, administrators etc.) in different social situations (paying taxes, getting married, sowing and harvesting, buying and selling, preparing for journeys etc.) and are written in different languages (Greek, Arabic and Aramaic) under different governments (Byzantine Christian and Arab Muslim). In short they are a fantastic resource for learning about the everyday life of a Near Eastern village as it passed from Byzantine to Arab rule, though, to Colt’s great disappointment, the disruptions of the Arab conquests in the 630s and 640s leave no trace in the papyri.

The Byzantine settlement of Nessana looking towards the acropolis

Despite its great worth this corpus has been surprisingly little studied, in part because only half of the papyri were edited and translated (albeit the more complete ones) and almost no images were included in the publication. Recently Roger Bagnall was successful in persuading the Pierpont Morgan library, where the papyri were deposited by Colt, to allow ISAW to digitize them and make them accessible on the web, which will greatly facilitate and encourage their study. To get the ball rolling, I, along with Hannah Cotton, Emeritus Professor of Classics at the Hebrew University, and Arietta Papaconstantinou, Professor of Late Antiquity at Reading University, will be initiating a project that will take a fresh look at the papyri and the village of Nessana, in particular taking account of the archaeological context.

The Byzantine settlement of Nessana looking towards the acropolis

Despite its great worth this corpus has been surprisingly little studied, in part because only half of the papyri were edited and translated (albeit the more complete ones) and almost no images were included in the publication. Recently Roger Bagnall was successful in persuading the Pierpont Morgan library, where the papyri were deposited by Colt, to allow ISAW to digitize them and make them accessible on the web, which will greatly facilitate and encourage their study. To get the ball rolling, I, along with Hannah Cotton, Emeritus Professor of Classics at the Hebrew University, and Arietta Papaconstantinou, Professor of Late Antiquity at Reading University, will be initiating a project that will take a fresh look at the papyri and the village of Nessana, in particular taking account of the archaeological context.

The material from Colt’s excavations was never subjected to close examination, and the extensive excavations in Nessana carried out by Ben Gurion University in the 1980s and 1990s were never published at all. There is therefore enormous scope for new insights into the history of this important little settlement and its environs during this pivotal period in the Near East.