Wine-making in the South Caucasus

I traveled to Georgia and Armenia this fall to conduct research and also to discuss with academic leaders there the Digital South Caucasus Collection, a project of the ISAW library that will make digitally available publications from the South Caucasus through the NYU library system.

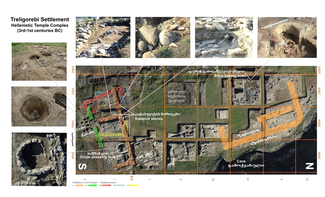

While in Georgia, I visited my colleague Mikheil Abramishvili (an ISAW VRS in 2008-09). We climbed a steep hill in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, to see his recent excavations of a third-first century BCE temple at the site of Treligorebi (Figure 1). One significant feature of the site is the number of large storage jars that once held wine; there is also a probably grape-pressing feature.

Fig 1. Treligorebi Settlement. Image courtesy of Mikheil Abramishvili

Winemaking has a long history in the South Caucasus, where there are many different varieties of grapes and many archaeological sites which have remains of wine-making. That grapes (and presumably wine) were important to Bronze Age inhabitants of the region is graphically demonstrated by the grapevines covered with silver that were retrieved in the excavation of Bedeni, Barrow 12, a very rich burial of the Early Kurgan Culture (Middle Bronze Age, 2nd half 3rd millennium BCE) (Fig. 2).

The traditional means of making wine in Georgia, in vessels known as qvevri, is in fact a UNESCO intangible Cultural Heritage.

Fig 2. Silver-covered grape-vine leaves. Image courtesy of The Simon Janashia Museum of Georgia. Photograph by Karen Rubinson

While traveling to eastern Georgia with Mikho with a pick-up and driver provided by the Georgian National Museum, we passed through the rich wine-making region at harvest-time. In search of modern qvevri, we happened upon a winery under construction that had several qvevri already buried into the floor (Fig. 3). I was told the largest of the vessels weighed two tons! A broken vessel nearby (Fig. 4) shows how the qvevri are used. They are lined with wax each year before the grape juice is added and washed out after they are emptied. In the Signaghi museum (the final destination of our eastern trip) there was a painted “Vintage” by the late 19th-early 20th century Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani that shows the washing out and filling of the jars (Fig. 5) in the early 20th century countryside.

While traveling to eastern Georgia with Mikho with a pick-up and driver provided by the Georgian National Museum, we passed through the rich wine-making region at harvest-time. In search of modern qvevri, we happened upon a winery under construction that had several qvevri already buried into the floor (Fig. 3). I was told the largest of the vessels weighed two tons! A broken vessel nearby (Fig. 4) shows how the qvevri are used. They are lined with wax each year before the grape juice is added and washed out after they are emptied. In the Signaghi museum (the final destination of our eastern trip) there was a painted “Vintage” by the late 19th-early 20th century Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani that shows the washing out and filling of the jars (Fig. 5) in the early 20th century countryside.

Fig 3. Winery under construction, Kakheti, Georgia. Photography by Karen Rubinson

Winemaking is an important economic activity in the South Caucasus today and both Georgia and Armenia have wine-making tour signs along their roads in the regions where grapes are grown, as I saw while driving through both countries. And the past of the process remains of great scholarly interest. In Armenia, a Chalcolithic site, Areni-1, was excavated in the last decade. And the University of Toronto has recently started a field project focused on the making of wine.

Winemaking is an important economic activity in the South Caucasus today and both Georgia and Armenia have wine-making tour signs along their roads in the regions where grapes are grown, as I saw while driving through both countries. And the past of the process remains of great scholarly interest. In Armenia, a Chalcolithic site, Areni-1, was excavated in the last decade. And the University of Toronto has recently started a field project focused on the making of wine.

Fig 4. Qvevri with remains of wax. Photograph by Karen Rubinson

Wine was a component of the hospitality my colleagues provided, together of course with the examination of archaeological sites, Bronze Age pottery, museum exhibits, and discussions about the Digital South Caucasus Collection.

Wine was a component of the hospitality my colleagues provided, together of course with the examination of archaeological sites, Bronze Age pottery, museum exhibits, and discussions about the Digital South Caucasus Collection.

Fig 5. “Vintage” Niko Priosmani, early 20th century. On display at the Sighnaghi Museum. Collection of the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts. Photograph by Karen Rubinson