Visiting Research Scholar Spotlight: Andrew Dufton

Most of us have an idea — especially in a city like New York — of what gentrification looks like. We’re familiar with the perceived influx of bearded hipsters across Brooklyn, completing freelance design projects on their MacBooks while drinking cold-brew coffees. We see the closure of smaller, independent groceries to make way for a Whole Foods Market or Trader Joe’s. Many of us are aware of the rising rents and property values in a neighborhood on the cusp of gentrification. As we spend our daily lives in a city undergoing various stages of gentrification, most of us have a preconceived idea of what gentrification means, and what it looks like.

My research during my first six months at ISAW has explored the ways that gentrification may have also been occurring in the Roman world, specifically in the cities of Roman North Africa. A boom in the construction of monuments and elite architecture from the 1st–3rd centuries CE has left a lasting impression on both scholars and tourists, and a great number of North African sites — cities such as Timgad (Algeria), Carthage (Tunisia), or Lepcis Magna (Libya) — are inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. We know less, however, of how residential spaces may have changed during this same period.

This work will be submitted for journal publication this spring, and I’ll next turn my attention to another urban process — sprawling growth — that has significance both in the ancient Mediterranean and in the modern world.

Read more about Andrew Dufton's research here.

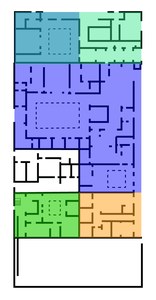

Phase plan of the Insula II at Utica, Tunisia.

Colored blocks show the consolidation of properties into larger, elite residences from the late 2nd century CE.