Archaeological Tourism in Mark Twain's "Innocents Abroad"

On January 15, the exhibition “A First-Class Fool: Mark Twain and Humor,” which I co-curated with Susan Jaffe Tane and Julie Carlsen and featuring items from Ms. Tane’s collection, opened at the Grolier Club. On the surface, it appears that this exhibition, focused on a figure firmly associated with the contemporary world of the nineteenth century, has little connection to antiquity. But Twain’s links to the ancient past become clear through one major theme of the exhibition: Twain’s extensive travel, which brought him from his birthplace on the Mississippi River to California, Hawaii, Europe, the Near East, and Australasia, to name but a few. “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry and narrow-mindedness,” he wrote, “and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts.” Twain chronicled these extensive journeys in a career-spanning series of books recounting his observations on the history and customs of the regions he visited. His discussions of history often extend to the ancient past, and his observations of traveler’s attitudes includes a biting critique of the archaeological tourism that was becoming increasingly popular in his day.

Twain’s first and most financially successful book, The Innocents Abroad, or, the New Pilgrims’ Progress, recounts the voyage of the steamship Quaker City, which in 1867 undertook a lengthy “pleasure-trip” to Europe, North Africa, and the Levant, making numerous stops at cities and historical sites of interest. Though not the first recreational cruise from America to the Eastern Mediterranean, the vessel’s journey was widely publicized, and the young Samuel L. Clemens, who had been writing under the name Mark Twain for just four years at that point, joined the trip on assignment for the San Francisco newspaper Alta California. The resulting book details every step of the journey (mapped by Stephen Railton at the University of Virginia), describing the sights the tour group saw, the people they encountered, and the legends recounted to them by their guides–all of these often skewered by Twain’s sardonic wit.

From the trip’s earliest stop at Gibraltar, Twain is frequently astonished by the antiquity of the locales he toured, commenting on a site in Tangiers:

Here is a crumbling wall that was old when Columbus discovered America; was old when Peter the Hermit roused the knightly men of the Middle Ages to arm for the first Crusade ; was old when Charlemagne and his paladins beleaguered enchanted castles and battled with giants and genii in the fabled days of the olden time; was old when Christ and his disciples walked the earth; stood where it stands to-day when the lips of Memnon were vocal, and men bought and sold in the streets of ancient Thebes!

'Old Roman,' from Twain's 'Innocents Abroad'

'Old Roman,' from Twain's 'Innocents Abroad'

But as his tour continues, it becomes clear that the denizens of these locales, both living and long-dead, interested him far more than the structures themselves. This is nowhere so clear as in his extended description of the Roman Colosseum, where he jokingly reports “discovering among the rubbish… the only playbill of that establishment now extant.” The document contains a description of gladiatorial combat in the grandiloquent style of a contemporary theatrical announcement, as well as a newspaper puff-piece reviewing the same event advertised by the playbill.

A more somber tone permeates Twain’s description of Pompeii, where he imagines the victims of Vesuvius’ eruption as his contemporaries:

Every where, you see things that make you wonder how old these old houses were before the night of destruction came—things, too, which bring back those long dead inhabitants and place them living before your eyes. For instance: The steps (two feet thick—lava blocks) that lead up out of the school, and the same kind of steps that lead up into the dress circle of the principal theatre, are almost worn through! For ages the boys hurried out of that school, and for ages their parents hurried into that theatre, and the nervous feet that have been dust and ashes for eighteen centuries have left their record for us to read to-day. I imagined I could see crowds of gentlemen and ladies thronging into the theatre, with tickets for secured seats in their hands… Hanging about the doorway (I fancied,) were slouchy Pompeiian street-boys uttering slang and profanity, and keeping a wary eye out for checks… These people that ought to be here have been dead, and still, and moldering to dust for ages and ages, and will never care for the trifles and follies of life any more for ever—“Owing to circumstances, etc., etc., there will not be any performance to-night.” Close down the curtain. Put out the lights.

Marble table from the 'House of the Prince of Naples' at Pompeii (VI.15.8), from Twain's 'Innocents Abroad'

Marble table from the 'House of the Prince of Naples' at Pompeii (VI.15.8), from Twain's 'Innocents Abroad'

He sees in these ancient sites enormous similarities to the people of his own day, focuses on the common humanity that links them, and laments the tragedy that ended their lives.

Twain frequently recounts legends that the group’s guides recount to them, never missing a chance to comment sardonically on errors and unlikelihoods. He regarded tales of religious relics and legends with particular scorn. While visiting Roman sites associated with St. Peter, for example, he remarks:

We stood reverently… in the Mamertine Prison, where [Peter] was confined, where he converted the soldiers, and where tradition says he caused a spring of water to flow in order that he might baptize them. But when they showed us the print of Peter’s face in the hard stone of the prison wall and said he made that by falling up against it, we doubted. And when, also, the monk at the church of San Sebastian showed us a paving-stone with two great footprints in it and said that Peter’s feet made those, we lacked confidence again. Such things do not impress one. The monk said that angels came and liberated Peter from prison by night, and he started away from Rome by the Appian Way. The Saviour met him and told him to go back, which he did. Peter left those footprints in the stone upon which he stood at the time. It was not stated how it was ever discovered whose footprints they were, seeing the interview occurred secretly and at night. The print of the face in the prison was that of a man of common size; the footprints were those of a man ten or twelve feet high. The discrepancy confirmed our unbelief.

The Quaker City trip had billed itself, in part, as a pilgrimage (as the subtitle to Twain’s book suggests), and its visit to Jerusalem and other sites in the southern Levant as its pious apogee. Twain himself seemed to be wearied by this stage of the trek, in part due to the proliferation of religious legends he encountered and in part due to his negative reaction to the poverty he witnessed throughout the Ottoman Empire, which then controlled much of the Eastern Mediterranean. His remarks on the desperate conditions on display frequently come across as xenophobic. (His thoughts on these subjects would evolve over time, and by the time of later works like Following the Equator and King Leopold’s Soliloquy he would focus his condemnatory eye on the imperialist causes of such poverty, rather than on revulsion at those who suffer from it.)

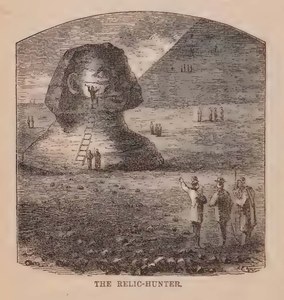

'The Relic-Hunter,' from Twain's 'Innocents Abroad'

'The Relic-Hunter,' from Twain's 'Innocents Abroad'

Twain is equally critical of the boorish behavior of his traveling companions, condemning those who carve their names on the ruins of Baalbek: “It is a pity some great ruin does not fall in and flatten out some of these reptiles, and scare their kind out of ever giving their names to fame upon any walls or monuments again, forever.” He mocks in particular one member of the Quaker City trip who traveled with a hammer that he used to break off chips of every monument and structure the group visited. But the vandal’s efforts were defeated by the sphinxes surrounding Pompey’s Pillar in Alexandria: “The relic-hunter battered at these persistently, and sweated profusely over his work. They regarded him serenely with the stately smile they had worn so long, and which seemed to say, ‘Peck away, poor insect; we were not made to fear such as you; in ten-score dragging ages we have seen more of your kind than there are sands at your feet: have they left a blemish upon us?’”

Twain is critical, too, of the overt racism of other travel books. In one chapter, he satirizes the writing of William C. Prime, whose 1857 book Tent Life in the Holy Land was recommended reading for participants on the trip. Burlesquing Prime with the pseudonym “Grimes,” he rebukes both the feigned piety and the casual violence of the prior traveler: “He went through this peaceful land with one hand forever on his revolver, and the other on his pocket-handkerchief. Always, when he was not on the point of crying over a holy place, he was on the point of killing an Arab. More surprising things happened to him in Palestine than ever happened to any traveler here or elsewhere since Munchausen died.” In an essay for the catalog published to accompany “A First-Class Fool,” scholar Alan Gribben quotes from the marginal comments that Twain penned in his personal copy of Prime’s book: “Always picturesque. Always an ass.”

But Twain was not uniformly dismissive of those who, as Gribben puts it, “had the audacity to arrive ahead of him.” He looked more kindly on what works of archaeological scholarship existed in the 1860s, drawing on Edward Robinson’s Biblical Researches in Palestine, and in the Adjacent Regions (1856) and David Austin Randall’s The Handwriting of God in Egypt, Sinai, and the Holy Land (1862). In comparison to the violent adventurism and phony reverence of Prime, Twain saw in these works a legitimate effort to capture what he had felt at Pompeii: an authentic link to the common people of antiquity.