From Protective Colophons to RFID Tags: A Brief History of Library Security

The role of the modern library is to preserve and provide access to information. There is a tension between these two goals: making sure that information is preserved for the future requires placing guardrails around how it can be accessed in the present. The ISAW Library’s solution to this problem is to make our collection non-circulating: our community may access the materials we hold inside our building. To ensure that these materials remain on-site– preserved for future readers– we use RFID (radio frequency identification) security tags. Any book that goes beyond our doors will set off an alarm, and the details of the item that triggered the alarm are sent to our security system. This system, installed in 2016, replaced an older, magnetic gate system in which potentially-purloined items would trigger an alarm, but no item details would be communicated.

The first magnetic security system – called “Tattle-Tape” – was developed in 1970 by 3M (which, as a division of Bibliotheca, provided our RFID security system). Prior to the development of this system, library security systems were less reliable. Often, they consisted of simply marking each book with ownership markings – a stamp or bookplate identifying the library as the rightful owner, discouraging theft by their passive presence. Often (as in these examples from our collection) they would indicate not only the book’s ownership, but also details about its shelving location and/or the donor who enabled its acquisition.

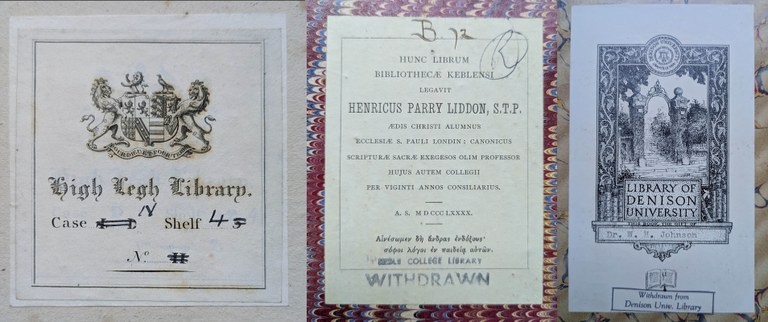

Bookplates from the ISAW Library's Antiquarian Collection: A bookplate from the High Legh Library in a 1740 edition of the plays of Terence (ISAW Antiquarian PA6755.A2 1740); from the Keble Library inside Keilinschriften und Geschichtsforschung by Eberhard Schrader (ISAW Antiquarian PJ3193.S37 1878); and from the Library of Denison University inside an 1885 edition of the works of Tacitus (ISAW Antiquarian PA6705 .A5 1885 v.1).

In recent years, as more and more libraries deaccession print materials from their collections, these markings can provide a challenge. Much of the ISAW Library’s collection was acquired at secondhand from the personal libraries of prominent scholars, and we continue to acquire materials from the secondhand market. Sometimes (as in the volumes from the High Legh Library and Denison University items above), the deaccessioning library has marked these items as withdrawn and cancelled out-of-date ownership markings. Just as often, however, these markings are left unaltered. When the ISAW Library encounters uncancelled ownership markings on books we’ve acquired at secondhand, we feel an obligation to reach out to the book’s former institutional owner to confirm that it is no longer their property. In most cases, they inform us that the book is no longer needed – but it has happened that we’ve sent books back to their proper owners, sometimes decades after they last resided in their proper homes.

Bookplates from the ISAW Library's Antiquarian Collection: A bookplate from the High Legh Library in a 1740 edition of the plays of Terence (ISAW Antiquarian PA6755.A2 1740); from the Keble Library inside Keilinschriften und Geschichtsforschung by Eberhard Schrader (ISAW Antiquarian PJ3193.S37 1878); and from the Library of Denison University inside an 1885 edition of the works of Tacitus (ISAW Antiquarian PA6705 .A5 1885 v.1).

In recent years, as more and more libraries deaccession print materials from their collections, these markings can provide a challenge. Much of the ISAW Library’s collection was acquired at secondhand from the personal libraries of prominent scholars, and we continue to acquire materials from the secondhand market. Sometimes (as in the volumes from the High Legh Library and Denison University items above), the deaccessioning library has marked these items as withdrawn and cancelled out-of-date ownership markings. Just as often, however, these markings are left unaltered. When the ISAW Library encounters uncancelled ownership markings on books we’ve acquired at secondhand, we feel an obligation to reach out to the book’s former institutional owner to confirm that it is no longer their property. In most cases, they inform us that the book is no longer needed – but it has happened that we’ve sent books back to their proper owners, sometimes decades after they last resided in their proper homes.

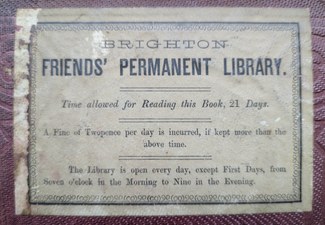

Sometimes, older ownership markings provide more details than just who the book’s rightful owner is. One book in the ISAW Library’s collection bears on its cover a prominent label from the Brighton Friends’ Permanent Library, indicating:

“Time allowed for Reading this Book, 21 days. A Fine of Twopence per day is incurred, if kept more than the above time.”

Label from the Brighton Friends' Permanent Library on a copy of Nineveh and Its Palaces by Joseph Bonomi (ISAW Antiquarian DS70 .B7 1852)

Label from the Brighton Friends' Permanent Library on a copy of Nineveh and Its Palaces by Joseph Bonomi (ISAW Antiquarian DS70 .B7 1852)

This label serves a dual purpose: It provides for the security of the book by identifying its rightful owner, but also details the terms of access (and the punishment for those who violate those terms).

Fittingly, this label appears on the cover of the book Nineveh and Its Palaces by Joseph Bonomi. One of the most important discoveries at the site of Nineveh was the Library of Ashurbanipal, assembled in the 7th century BCE. The materials in this library display a similar concern with security and access.

Much of our knowledge concerning Ashurbanipal’s library derives from colophons on many of the tablets it contained. Some of these trace the history of the library itself and Ashurbanipal’s mission of assembling all of the knowledge available to him in written form. These colophons follow several formulaic patterns, some of which seem particularly concerned with the physical safety of the tablets and their identification as Ashurbanipal’s property:

“Whoever takes (this tablet) away, or writes his own name instead of mine, may Ashur and Ninlil wildly and furiously reject him, and make his name and seed disappear from the land.” (Ashurbanipal Library Colophon C, BAK 319, included on tablet K.43/CDLI P393726)

“I have written, checked and collated this tablet in the assembly of scholars, and placed it in my palace for my royal consultation. Whoever erases my name and writes his own, may Nabu, scribe of everything, erase his name!” (Ashurbanipal Library Colophon B, BAK 318)

“Excerpt tablet of Ashurbanipal, King of the World, King of Assyria, descendent of Sennacherib ... Sargon, King of the World ... Whoever might take it and alter my inscription, [may] Ashur, king of the gods [remove his] name [and seed from the land].” (Ashurbanipal Library Colophon U, BAK 333)

The concern with protecting the place of Ashurbanipal's name, alongside the invocation of the gods, suggests a divine purpose to these ownership inscriptions. The king's name indicates not merely rightful possession of the physical tablet, but also divine sanction to access and control the knowledge of the tablet itself.

Other scholarly texts from Hellenistic Mesopotamia bear similar imprecations, invoking the gods to discourage theft.

“Tablet of Anu-bēlsunu, lamentation priest of Anu, son of Nidinti-Anu, descendant of Sin-leqi-unninni, Urukuean… Whoever reveres Anu, Ellil and Ea shall not take it away by theft.” (TCL 6, 12+, quoted in Stevens, "Secrets in the Library," p. 211; tablet details at https://cdli.earth/artifacts/363685)

In addition to theft, others warn against loss, while occasionally making provision for short-term loan:

“Whoever reveres Ansar and Kisar shall no[t ta]ke (it) away, or deliberately let it be forgotten.” (SpTU 2, 8, quoted in Stevens, "Secrets in the Library," p. 241)

“Whoever reveres Anu, Ellil and Ea shall not take it away, shall not deliberately let it be lost. On the same day he should return it to its owner's house. Whoever takes it away, may Adad and Sala take him away.” (SpTU 2, 6, quoted in Stevens, "Secrets in the Library," p. 244)

In his book Secrecy and the Gods, Alan Lenzi calls these palih colophons, based on their formulaic use of the word palih, a word associated with reverence and fear of the gods, in invoking the protection of specific deities. But he notes that they are sometimes paired with a different kind of protective colophon: a Geheimwissen colophon, which demands that the knowledge encoded on the tablet remain secret:

“An expert may show an(other) expert. A non-expert may not see it.” (TCL VI 32, quoted in Lenzi, Secrecy and the Gods, p. 202)

“(Whoever fears…) shall not cause it to be unavailable (from use by its owner?). He shall return it in its proper time to the house of its owner. The one who carries it off, may Sala carry him off. An expert may show an(other) expert. A non-expert may not [see it].” (SpTU 4, 147, quoted in Lenzi, Secrecy and the Gods, p. 203)

These colophons display a dual concern for the physical safety of the material object bearing the text and for the place of the specialist in elite society. Kathryn Stevens comments that these experts “marked at restricted the particular body of knowledge at the heart of their respective disciplines” (Stevens, "Secrets in the Library," p. 231).

Similar restrictions appear in later papyri originating in Egypt. The Greek Magical Papyri are particularly concerned with the secrecy of their contents: The Tenth Hidden Book of Moses begins with an exhortation to secrecy:

“When you have learned the power of the book, you are to keep it secret, child, for in there is the name of the lord, which is Ogdoas, the god who commands and directs all things, since to him angels, archangels, he-daimons, she-daimons, and all things under the creation have been subjected.” (PGM XIII 734-1077)

Early Christian monastic libraries, too, were concerned with protecting knowledge. The fifth book of Shenoute’s Canons states:

“If we need to have a look at or to copy some books that we do not possess, we shall not be permitted to seek them from outside the congregation without permission of the father superior. And if we are brought books from outside the congregation that are suitable to read, or letters, we shall not give them to anyone among us unless we have informed him about them. Nor shall any person among us read them under any circumstances without first telling him. For indeed, perhaps there are some words in them that people ought not to hear.” (The Canons of our Fathers, book 5, rule 245, trans. Bentley Layton)

The concern here is not so much with keeping secure books themselves or the knowledge they contain, but rather keeping the minds of potential readers safe from dangerous ideas.

The contemporary librarian can understand the desire for security to preserve information for future readers, but the elitist and secretive demands of many of these colophons strike us as regressive. In the era of Open Access, we seek to preserve materials for the future so that all may access them.

Another corpus of ancient texts is perhaps closer to modern conceptions of free circulation of knowledge. colophons in some of the Buddhist manuscripts from Dunhuang encourage the copying and dissemination of texts. The copying of a religious manuscript was considered a virtuous act, and many of these texts contain statements by their scribes detailing their work. On one 6th-century manuscript, a female scribe named Jianhui announces:

“[I] respectfully make one copy of the [Sutra on the Buddha’s] Entrance to Lanka, one copy of the [Sutra of the] Dharma Blossom, one copy of the [Sutra of the Queen of the] Wondrous Garland, one copy of the [Sutra of the Buddha of] Immeasurable Life, one copy of the [Scripture for] Humane Kings, one copy of the [Extensive Scripture], and two copies of the [Scripture of the] Medicine [Buddha]… Jianhui completes the respectful copying, circulates, and venerates it.” (BD15076, Quoted in Chen, “Determining the Authenticity of Dunhuang Colophons,” p. 66-67)

Here we see a better analog to our contemporary ideas, and even a precursor to the digital preservation principle known by the abbreviation LOCKSS: “Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe.” The ancient scribe, like the modern librarian, has a duty to respectful circulation and reverent preservation– dual goals that the plain, humble squares of our RFID tags seek to facilitate.

Bibliography

Betz, Hans Dieter. “Secrecy in the Greek Magical Papyri.” In Secrecy and Concealment: Studies in the History of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Religions, edited by Hans G. Kippenberg and Guy G. Stroumsa. Studies in the History of Religions 65. Brill, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004378872_012.

Betz, Hans Dieter, ed. The Greek Magical Papyri In Translation. 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press, 1986. https://n2t.net/ark:/13960/t9963gp01.

Chen, Ruifeng. “Determining the Authenticity of Dunhuang Colophons: Practical Procedures Derived from a Study of Three Colophons Employing Similar Templates.” T’oung Pao 110, nos. 1–2 (2024): 54–105. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685322-11001004.

Hunger, Hermann. Babylonische und assyrische Kolophone. Alter Orient und Altes Testament, Bd. 2. Butzon u. Bercker, 1968. https://search.library.nyu.edu/permalink/01NYU_INST/1d6v258/alma990040708490107876.

Lenzi, Alan. Secrecy and the Gods: Secret Knowledge in Ancient Mesopotamia and Biblical Israel. State Archives of Assyria Studies 19. Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 2008. https://search.library.nyu.edu/permalink/01NYU_INST/1d6v258/alma990034341810107876.

Stevens, Kathryn. “Secrets in the Library: Protected Scholarship and Professional Identity in Late Babylonian Uruk.” Iraq 75 (January 2013). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021088900000474.

Taylor, Jonathan. “Library Colophons.” Reading the Library of Ashurbanipal Project, The British Museum, 2022. https://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/asbp/rlasb/Librarycolophons/index.html.

Thanks to Samantha Rainford for cuneiform text assistance.