ISAW Library Internship Report: Expanding a Linguistic Dataset of Women-authored Latin

A guest post by Margaret Ratzan, Willa Romer-Mack, and Lily Hegener, with an introduction by Associate Research Scholar Patrick J. Burns, reporting on Spring 2025 internships in the ISAW Library working on the Representing Women Authorship in the Latin Treebanks (RWALT) project.

Spring 2025 was an exciting time for the Representing Women Authorship in the Latin Treebanks (RWALT) project. The project has begun to attract attention from outside of ISAW Library in the form of two roundtable presentations, the first as part of a RELICS online discussion on “Women as Authors of Latin Literature” and the second at the Renaissance Society of America conference as part of a pedagogy-themed discussion on “Teaching Neo-Latin Texts by Women: Strategies and Innovations in Latin Education”. The RSA roundtable also received support in the form of a Professional Development grant from the Classical Association of the Atlantic States. Second, the project continued to grow both with respect to the number of women Latin authors covered and in the number of text annotations recorded. As you will read below from the contributors themselves, we extended our high-school internship program into the spring with Lily Hegener continuing and Margaret Ratzan and Willa Romer-Mack joining the RWALT team.

This spring I worked with Patrick Burns on the RWALT project to read, translate, and annotate Isotta Nogarola’s 1451 De Pari aut Impari Evae atque Adae Peccato, that is the Defense of Eve. Not only was this work the first piece of Latin written by a woman that I have ever read, but it is also the first Latin feminist work that I have ever encountered (though not without its share of misogyny). In the work, Nogarola not only defends Eve, arguing that she is not at fault for the original sin, but also goes so far as to blame Adam.

The Defense is also the first piece that I have read while working directly with the computer and I have enjoyed learning about the LatinCy program, gaining a better understanding of how both humans and computer programs process language. While correcting the LatinCy annotations, I became curious about why the Latin word est ("is") wasn’t being labelled as a verb (VERB) but as an auxiliary (AUX). I quickly reconciled this with the fact that est was often part of a compound verb and so not like the other verbs. It isn’t active or passive like other verbs and works differently with other words. I started to question whether the program was simply taking each word out of context and parsing it, or if the program could really tell whether a construction like ausus est (“dared”) was truly seen as one compound verb. As I learned more about the program and how to read all the information it spits out, I discovered that indeed the computer comes to “know” that certain words belong together and, in a way, can “read” the sentence as a whole rather than as just a collection of discombobulated parts. When one puts a sentence into the processing pipeline, one step in that process is sentence parsing. Using this parser, the program will actually identify a root and then almost diagram the sentence, marking which words rely on others, and in this way, see that something like ausus est is a unitary construction.

Turning to the Defense as a piece of literature, the most interesting argument in it for me went hand-in-hand with the work I was doing as a word-by-word annotator. At one point Nogarola starts to quote from the Bible, and while annotating one starts to notice that all of the imperative verbs are singular and all of the adjectives singular and masculine. In line with these morphological observations, Nogarola points out that God only ever commanded Adam (singular and masculine) not to eat the fruit from the tree of knowledge, not Adam and Eve (plural); and therefore original sin only occurred after Adam had eaten from the tree, not Eve. This argument was to me convincing, as the grammar implies that Eve was never personally enjoined from eating the fruit.

This experience has been wonderful not only for getting to read some new (for me) and interesting Latin, but also for being able to learn about how computer programs can understand language. I want to thank Patrick Burns for guiding me through this internship and his constant enthusiasm to answer my relentless questions.—Margaret Ratzan

In my work this spring with Patrick Burns and David Ratzan on RWALT, I read, translated, and produced annotations for two works: the praefatio of Proba’s Cento Vergilianus as well as an excerpt from Maria Sibylla Merian’s 1719 De generatione et metamorphosibus insectorum Surinamensium, that is The Birth and Changes of Insects in Surinam.

Proba’s 4th-century cento assembles lines from Virgil into a new work, a retelling of biblical stories including the life of Christ. But the preface is her own writing, an explanation of how she came to her new project. But the part of this spring’s internship that I was most passionate about was the work of Merian: both her beautifully detailed scientific descriptions and illustrations.

Merian’s work details plants, animals, and flowers encountered by the author herself in Surinam. I was introduced to Merian’s writing accidentally while compiling metadata for the RWALT database. I was immediately drawn to her work. Alongside classics, two of my great interests are art and ecology, and finding Merian’s work was the perfect intersection of these interests. Between her Latin writing, vivid scientific descriptions, and intricate illustrations of the plants and animals she encountered, Merian felt like the perfect match for me to work with. Some of my favorite Latin and Greek writing I have read in my classes are the incredibly vivid (and sometimes gory) descriptions of battles and landscapes in Vergil’s Aeneid and Homer’s Odyssey—Odysseus’s battle with Polyphemus is a personal favorite. Being able to read such vivid, descriptive Latin that was written by a woman was such a wonderful experience that allowed me to feel even closer to the text and excited about the prospect of making an unheard voice in Latin literature more accessible.

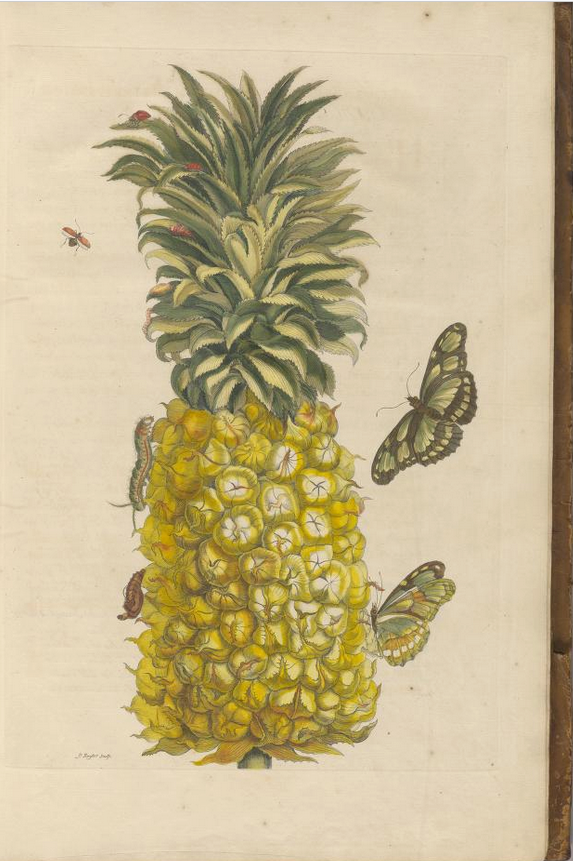

There is so much more to do with the Merian text. My work this past Spring looked at fruit like the pineapple and insects like butterflies and ladybugs (see the picture below), but the title page promises toad, lizards, snakes, spiders and alia admiranda istius regionis animalcula (“other marvelous little animals from this part of the world”). There are even some pre-Darwin illustrations of the transformation of a frog into a fish (and a fish into a frog). I am incredibly grateful to have had the chance to engage with Merian’s writing thanks to the RWALT project.—Willa Romer-Mack

An illustration of the ananas fruit (that is, the pineapple) from Surinam with insects including butterflies and ladybugs from Figure 2 of Merian’s De generatione et metamorphosibus insectorum Surinamensium. Picture from Internet Archive.

An illustration of the ananas fruit (that is, the pineapple) from Surinam with insects including butterflies and ladybugs from Figure 2 of Merian’s De generatione et metamorphosibus insectorum Surinamensium. Picture from Internet Archive.

In my continued work this spring with the ISAW Library on the RWALT project, I read, translated, and annotated Luisa Sigea’s Epistula 14 and Syntra. The Syntra is a Latin pastoral dialogue set in the Portuguese countryside, where Sigea served as a maiden for the Infanta Maria. In the poem, Sigea brings mythological figures like dryads and nymphs, as well as Ceres and Pan, to lush Portuguese landscapes, helping to highlight the enduring importance of classical literature and imbuing it with Christian values. After finishing my work on the Syntra, I came to see it as a work that celebrates intellectual capacities: it deeply reflects Renaissance ideals, honing in on the human potential–regardless of gender.

There was one moment that especially resonated with me. While reading Epistulae 14 with Patrick, we noted how much it read like a modern-day email, reflecting on its comments about procrastination (Ep. 14.1: procrastinationis veniam supplex expostulo, “On bended knee, I beg forgiveness for procrastinating”). As I’ve worked with Sigea for about a year now, her Epistulae have helped me to appreciate how she wrote not only of large ideas and overarching themes, but also about everyday challenges that people faced–and still do!

I want to thank Patrick and David for their continued support and guidance while I interned for them throughout my sophomore year. Their kindness, expertise, and unwavering willingness to help has not only developed and deepened my passion for Latin, but has truly shaped me as a Classics student.—Lily Hegener

Pineapple image from Internet Archive.