Corpus of the Inscriptions of Campā

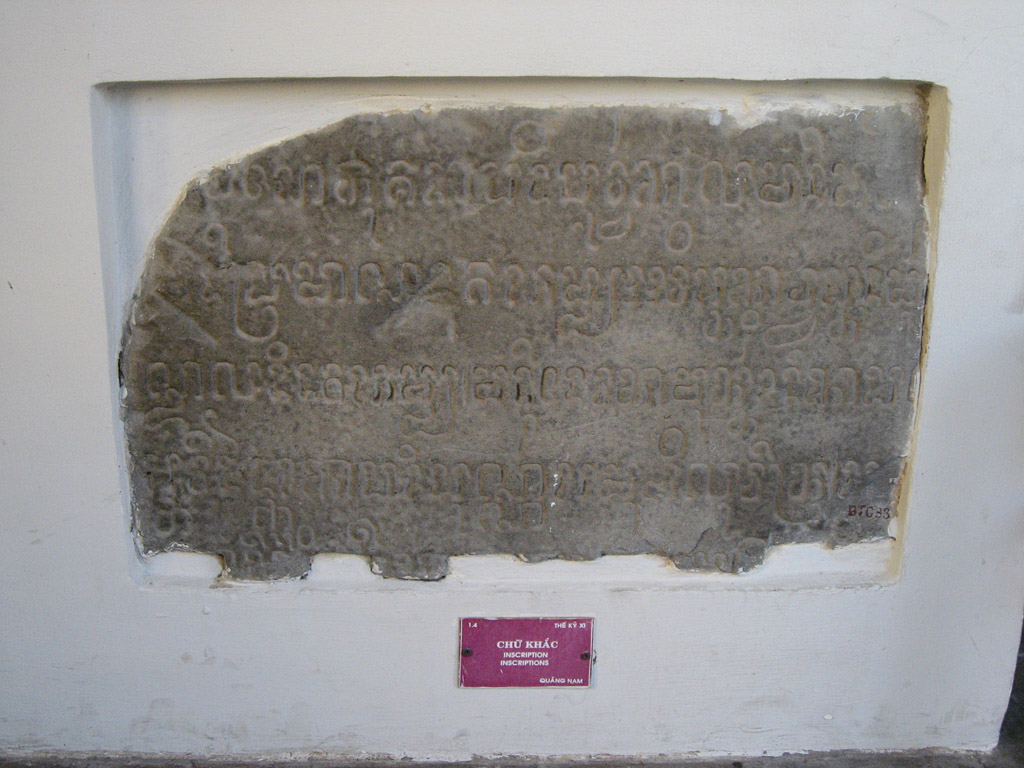

C. 64 Broken boulder of Chiên Đàn

Please note: you are reviewing a preprint version of this publication. Contents here may change significantly in future versions. Scholars with specific interests are urged to consult all cited bibliography before using our texts and translations or drawing other significant conclusions.

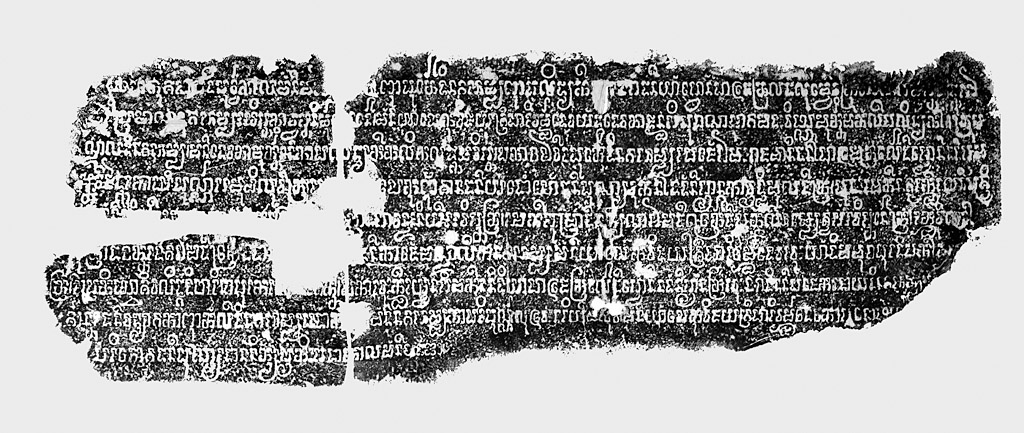

Support Large boulder; sandstone. Dimensions of the original stone h. 80 cm × w. 240; of the fragment in the museum (A): h. 51 × w. 85 × d. 44; of the fragment still in situ (B): h. 94 × w. 190 × d. 80.

Text Nine lines on one face written in Old Cam.

Date early 11th century CE.1

Origin Temple of Chiên Đàn (Quảng Nam).

This boulder was found before 1892, when it was first mentioned in the literature (Paris 1892: 141), and said to have been observed at the “towers of An-don”; mentioned again in 1896 (Aymonier 1896a and Aymonier 1896b: 94) as “inscription of Qua My, at 60 km to the South slightly eastward of Tourane”, and tentatively assigned to the 11th century CE. The inscription was inventoried as C. 64 in Cœdès 1908: 44, in association with place name Hoà-mi; inscription and stone were inventoried Parmentier 1909: 278, correctly attributed the Chiên Đàn site (here spelt Chiên Đàng), and assigned to the late 11th century CE. Moved by C. Paris to his concession in Phong Lệ in 1900, and from there to the antiquities park in Tourane in 1901. Registered in the Tourane Museum in 1919, with inventory number 1,4 (Parmentier 1919: 12), that was subsequently mentioned in the improved inventory of inscriptions (Cœdès 1923). We identified fragment A encased in a wall of the Đà Nẵng Museum in 2009. It has since then been removed from the encasing and according to our latest information is now kept in storage. We observed fragment B in situ on 20 September 2009. We were unable to find fragment C during any of our visits to Vietnam since 2009.2

Edition(s) First published, with French translation, in Schweyer 2009a: 41-45; newly edited, with translation into English (and Vietnamese), in Đà Nẵng Catalog: 219-224; whence the present edition.

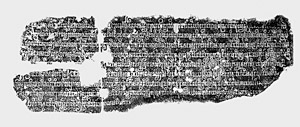

Facsimiles

- Estampage: EFEO 31

- Estampage: EFEO n. 266

The following text was edited by Arlo Griffiths and Amandine Lepoutre.

(2) ⫷⫸(ma)ṅ· pramāṇa (na)gara campa avista kā dhvasta nirmū⫷⫸[la] nau | mam̃n· yām̃ po ku vijaya śrī harivarmmadeva yam̃ṅ[·] devatājanma sī purāṇa āgama daḥ viṣṇumūrtti matam̃l· paliṅyak· (śa)truma-

(3) ⫷⫸ṇḍala di nagara campa | mam̃n· devatāmūrtti nan· kā pa(l)⫷⫸[i]ṅyak· kalikalaṅka avista | pakā bharuv· ra putau di nagara campa ra pajem̃ rumaḥ rājadhānī ṅan· hajai tralauṅ· svon· ṅan· sama-

(4) ⫷⫸stavījāṅkura kā paripūrṇṇa samū dhiluv· tra | (pa)[kā yām̃] ⫷⫸ po ku īśāna ṅan· ya doṁ yām̃ ṅan· puṇya vukan· dadam̃n· sthāna kā vṛddhi mulaṅ· tra | punaḥ ra mak· nagara kmīra lac· paści-

(5) ⫷⫸ {17} ⫷⫸ (sāra) sā vandaḥ niy· avista tra | ra mak· sumrāṅ· dakṣiṇa rumaṅ· krauṅ· patam̃l· campeśvara avista nau tra | ra tmuv· lac·

(6) ⫷⫸ [s]u(m)rāṅ(·) uttaradiśa rumaṅ· kr(auṅ·) dā {5} ⫷⫸ (na)n· kā jem̃ maṇḍalīka nagara campa mam̃n· yā(m̃) po ku vijaya śrī harivarmmadeva ra vuḥ yām̃ di madhurāpura di pak· (duna)[n·]

(7) ⫷⫸ tra | ra pratiṣṭhā śivaliṅga di harināpura ka(ra)[ṇā] (k)[īr]tt[i] | ⫷⫸ (pa)kā ra vuḥ kmīra yvan· si mak· nan· di yām̃ hajai tralauṅ· svon· dadam̃n· sthāna tra ra vuḥ urām̃ dinan· pajem̃ karadā yam̃ di nagara campa {3-4}

(8) ⫷⫸ [de]śāntara ṅan· vanyāga kā ñu tam̃l· di nagara campa (sa)dāk[āla] ⫷⫸ mam̃n· nagara campa kā paripūrṇṇa luvaiḥ nariy· dhīluv· | ma(m̃)n· yām̃ po ku vijaya śrī harivarmmadeva kā (sa)n[t]o[ṣa] {3-5}

(9) ⫷⫸ {2-3} paribhoga ṅan· puṇyadāna nityapṛtiḥ sadā⫷⫸(kā)la mam̃n· || ((quatrefoil)) ||

1 || hetu śanāpa ◇ ⊙ {1}pākuśadā {1} Schweyer. — ma(d)[ā urām̃] (kā) ◇ ma[dā] ñū Schweyer. There are certainly more akṣaras lost between the two fragments than Schweyer supposes. The concrete sequence of words we conjecture here, mam̃n madā urāṅ kā ñu putau, is found also in C. 30A1, l. 4. — putau ◇ puitau Schweyer. — campa ñu ◇ campā ñū Schweyer. — [naga](ra) urā(m̃) ◇ {3} rā Schweyer. — 1-2 tral[au]ṅ[·] lumv(auv)[·] kru[vau ṅan·] sama(s)ta[vījā]ṅkura ru(ma)ṅ· ◇ tralaṅ lumve{1} tra {7} kā {1} di Schweyer. — 2 campa ◇ campā Schweyer. — kā dhvasta ◇ (kāvvasta) Schweyer. — nau | mam̃n· ◇ nau măn Schweyer. — po ◇ pŏ Schweyer. The cases of po in this inscription are all plain, without any added diacritic in the original, so there is no need for any diacritic in the transliteration either. — yam̃ṅ[·] ◇ yā(ṅ) n Schweyer. — campa | ◇ campā | Schweyer. — 3 pakā ◇ (ṅ)a kā Schweyer. — campa ◇ campā Schweyer. — svon· ṅan· ◇ svon nan Schweyer. — 3-4 samastavījāṅkura ◇ sta (vajustta) Schweyer. — 4 (pa)[kā yām̃] ◇ (sa) {2} (yāṅ) Schweyer. — ya ◇ yă Schweyer. The estampage is a bit deceptive here, for the stone clearly shows that the akṣara does not bear the anusvāra-candra sign. — puṇya ◇ pūṇya Schweyer. The estampage is a bit deceptive here, for the stone clearly shows that the vowel is short. — vukan· ◇ (sukan) Schweyer. — mulaṅ· ◇ mulan Schweyer. — punaḥ ra mak· ◇ punaḥ mak Schweyer. — kmīra ◇ kmira Schweyer. — lac· paści- ◇ {2} paśyi Schweyer. — 5 (sāra) sāvandaḥ ◇ saranda Schweyer. — sumrāṅ· dakṣiṇa rumaṅ· krauṅ· ◇ (sumrāṅ dukyaṇarumaj) rā krauṅ Schweyer. Schweyer has misread the leftward extension of the r in krauṅ· as rā. — tmuv· lac· ◇ tmuv la {2} Schweyer. — 6 [s]u(m)rāṅ(·) uttaradiśa rumaṅ· ◇ {2} krāṅ uttarad śarumaṅ Schweyer. — kr(auṅ·) dā {5} (na)n· kā ◇ krauṅ ṅa{n} {7}n kā Schweyer. — maṇḍalīka ◇ maṇdalika Schweyer. — campa ◇ campā Schweyer. — di pak· (duna)[n·] ◇ di para(.)ra Schweyer. — 7 ka(ra)[ṇā] (k)[īr]tt[i] ◇ tara{4}tta Schweyer. The expression karaṇā kīrtti is found in several other inscriptions (C. 30A1, l. 23; C. 75, l. 3; C. 120, face B, l. 6) and can clearly be reconstituted from the parts of akṣaras that remain here. — (pa)kā ◇ sa kā Schweyer. — kmīra ◇ kmira Schweyer. — yvan· ◇ yvăn Schweyer. — si ◇ sei Schweyer. There is no anusvāra-candra above the akṣara in question to justify Schweyer's reading. — tralauṅ· ◇ tralaṅ Schweyer. — tra ra vuḥ ◇ tra | vuḥ Schweyer. — dinan· ◇ nan Schweyer. — karadā yam̃ ◇ karadāya Schweyer. — campa {3-4} ◇ campā Schweyer. — 8 [de]śāntara ṅan· vanyāga kā ñu ◇ {1} śāntaḥ ṅan· vadyāg(.)ata kāñu Schweyer. — campa ◇ campā Schweyer. — (sa)dāk[āla] ◇ nan (dāka) {2} Schweyer. — campa ◇ campā Schweyer. — luvaiḥ nariy· dhīluv· | mam̃n· ◇ luvai{1} niy (maluva) măn Schweyer. — 8-9 kā (sa)n[t]o[ṣa] {3-5}{2-3} paribhoga ◇ kā ra {5+3} pari(.)ośa Schweyer Schweyer. Cf. C. 94, face B, ll. 1–2: yāṅ po ku vijaya śrī harivarmmadeva kā santoṣa nirākula dauk aṅguy rājaparibhoga. The passage can very likely be restored on the basis of the elements in this parallel passage, but the present inscription seems to have had a slightly shorter formula, since the lacunae cannot have offered space for all of the akṣaras seen between santoṣa and paribhoga in C. 94. — 9 nityapṛtiḥ ◇ nītya sṛtiḥ Schweyer. Understand nityaprītiḥ. — mam̃n· || ((quatrefoil)) || ◇ Schweyer notes an illegible syllable before the quatrefoil. But we think it is more likely that the text ends with mam̃n·, after which follows a complex of (non-akṣara) terminal symbols. This appears to the case also at the end of C. 210, face D, although the reading there is not clear either. On C. 119, face B, the text ends with sadākāla mam̃n· niś(c)aya ||, but we certainly cannot have a full word like niścaya after mam̃n· here.

Translation

(1–2) Because of a curse in the past, for that reason there was a man who became king in the Campā country, who robbed the country, the people and the gods of the citadel of Tralauṅ Svon, the cows, the buffaloes. And all seeds and sprouts, from all the provinces of the Campā country, then went to radical annihilation.

(2–3) After that Y.P.K. the victorious Śrī Harivarmadeva, who is of divine birth — namely, [according to] the Purāṇas and Āgamas, an incarnation of Viṣṇu —, succeeded in expelling the coalition of enemies in the Campā country. Thereupon that divine incarnation went on to destroy all faults of the Kali (age).

(3–4) Only then (pakā bharuv) he was king in the land of Campā. He built an abode as capital and [he rebuilt?] the citadel of Tralauṅ Svon. And then all seeds and sprouts also (tra) became prosperous as before.

(4) Then my lord the god Īśāna and all the other gods and religious foundations (puṇya), of various places, also prospered again (?, mulaṅ).

(4–7) In turn he took the lac land of the Khmers country in the west ... all of this one part too. He took all of Southern direction from the river to Campeśvara too. He met (?) lac the northern direction, from the river ... then became vassals of the land of Campā. After that my lord his victorious majesty Śrī Harivarmadeva also offered to the gods of Madhurāpura in those four [directions]. He installed a liṅga of Śiva at Harināpura to make fame.

(7–8) Then he offered those Khmers and Viets whom he had captured to the gods of the citadel of Tralauṅ Svon [and those] of various [other] shrines too. He ordered these men to make subject to the taxes of the Campā country ... foreigners and the traders who arrive in the Campā country, always.

(8–9) So the Campā country became even more prosperous than before. Then my lord his victorious majesty Śrī Harivarmadeva became satisfied ... (royal) property and meritorious gifts, permanent pleasure, always!

Commentary

Secondary Bibliography

- Majumdar 1927: 195.3

- Golzio 2004: 163-164.4

Notes

- We believe that this inscription is to be dated earlier than previous scholars have assumed. See Cf. ECIC III: 454 n. 36.

- From the earliest references, the sources speak of an inscription in three fragments. Parmentier 1919 suggests that the original rock was willfully split into three fragment “at the hands of the coolies of Paris”; he mentions that the fragment held in the Museum had been “detached from the block and transported at the order of C. Paris to his concession of Phong-lệ before 1900; brought to the Tourane Garden in 1901 and registered under the provisional number n° 105”. We think that these accusations of vandalism may not be fair, because Camille Paris himself, in the first ever report of the inscription, clearly states that the stone was already broken in three pieces when he found it. For reasons unknown to us, this report is not cited in any of the publications of Parmentier and Cœdès, and could thus come to be forgotten by subsequent generations of scholars.

- With outdated attribution to a site “Hoà Mi”.

- Attributed to a site “Hoà Mi-Chiêm Dang” (sic).

This theme of a curse (śanāpa) is expressed also in other inscriptions. Cf. e.g. C. 89, face B, l. 16: ... hetu śanāpana ... Other expressions that seem noteworthy in the present inscription are also shared with that text. See e.g. C. 89, face B, l. 20: ra vuḥ urāṅ ṅan lumvau kruvāv ṅan samasta upakaraṇa panūjā devatā dinan. We also find noteworthy parallels in C. 94. See face A, l. 19: rā pajeṅ .... śvan tralauṅ ṅan samastavījāṅkura... The word śatrumaṇḍala, found here in lines 2–3, is also seen in C. 94, face A, ll. 1 and 12 and C. 89, face B, l. 8; it may further be compared with mandala śatruḥ in C. 19, l. 9.

The sequence svon hajai tralauṅ in our inscription seems to be an error for hajai tralauṅ svon: cf. lines 3 and 7, as well as C. 95, face B, ll. 17–18. On the word purāṇa in connection with what seems to have been a different king Harivarman than the one of the present inscription, cf. C. 100 B, l. 12: etena purāṇārthena lakṣaṇenaitad gamyate śrī jaya harivarmmadevo yaṁ sa uroja eveti || and stanza XVII: śivānandanaśabdasya dṛṣṭenārthādriṇā kṣitau urojo lokavācyo yaḥ purāṇārthena lakṣaṇī ||.